Project tests new ways to deliver climate messages to farmers' cell phones

One of the big questions that should be exercising minds at the current Climate Talks in Poland is how smallholder farmers can better manage climate risks. One solution that has been discussed at length - and tried widely - is using mobile phones to deliver climate-related information to farmers; it is seen as being an efficient, cost-effective and quick way to get targeted messages to large audiences such as smallholder farmers.

But are the gains from this type of information dissemination as obvious as they appear?

Does writing or recording a message, punching in a number and pressing send really transform farmers’ abilities to cope with erratic weather events or their willingness to adopt climate-smart agricultural practices?

How Can text and voice messages really transform farmers' abilities to adapt to Climate change? Photo: F. Fiondella (IRI)

Study finds weaknesses in mobile-based information services

A 2011 study by researchers from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) found that this is not always the case. Surabhi Mittal and Mamta Mehar found a number of crucial gaps and limitations in current advisory services being delivered by mobile phone to farmers in the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

For instance, content in messages was often not tailored to the local needs of farmers. The study found that farmers are keen to get very specific information, such as how to manage pest attacks or specific crop varieties that are more climate-resilient, rather than general advisories on the weather or pesticide use.

The study also highlighted that, without the support of additional institutions, such as markets, credit institutions, warehouses and storage facilities, messages on their own do not bring about much change.

Learning from mistakes

Following up on this CIMMYT study, the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and CIMMYT are implementing a pilot project aimed at improving delivery of climate-related information to farmers in Karnal in Haryana and Vaishali in Bihar, ‘climate-smart villages’ that are baseline sites for CCAFS research in the region. IFFCO Kissan Sanchar Limited, a telecom content provider, and Kisan Sanchar, an implementing agency, are key project partners.

Crucially, the project will measure the real impact of the service it provides and assess whether it will be sustainable once external funding ends.

The project is sending voice and text (SMS) messages in Hindi to farmers’ mobile phones. These are aimed at encouraging farmers to adopt technologies that can mitigate climate risks.

Messages include weather forecasts and recommended actions that farmers should take, and information about pests and remedies, seed varieties and climate-smart technologies such as conservation agriculture. Additional messages provide up-to-date- market information and contact details for seed providers such as the Haryana State Cooperative Supply and Marketing Federation Limited.

Started in August 2013, the project currently reaches out to 1200 men and women farmers in eight villages and will run for eight months at a pilot level.

The right time and the right people

There is always a right time to send a message. When information is not timely it is pretty much useless. In the 2011 study, farmers who received an SMS alert warning them that traces of rust, a disease that can ravage wheat crops, had been found in some fields in their neighbourhood were able to take preventive measures and avoid crop losses. By engaging closely with enrolled farmers, the project is ensuring that its messages are timely and address issues facing farmers.

Similarly, a messaging service will only be useful if it reaches an interested audience. Often message services assume that all farmers want their information and fail to assess individual needs and preferences.

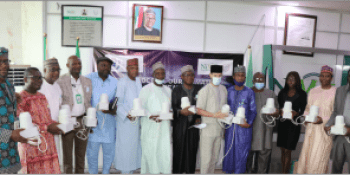

The project in India is working with government officials to ensure women also participate in the pilot study. Photo: Surabhi Mittal (CIMMYT)

The CCAFS-CIMMYT pilot project is addressing this issue by gathering specific information about each farmer enrolled in the project, including the size of their land holdings, the crops they grow, the types of seeds they use, their age, education and so on.

One of the hurdles the project had to overcome was how to get women farmers to volunteer their details, given cultural and social barriers. It achieved this by approaching the village elected heads and women government officials and engaging their support in encouraging women to participate. In Bihar, a woman scout leader mobilized women farmers who are now engaged in the project.

A two-way street: farmers can call in

Many message-delivery systems are a one-way street—designed to ‘push’ information to the audience. But the CCAFS-CIMMYT pilot project is designed to be a two-way street—farmers can call a helpline and ask questions, allowing them to ‘pull’ the information they need, when they need it.

Where possible, the questions are dealt with right away but some more challenging queries are forwarded to an expert, who responds to the farmer as soon as possible. By analysing the types of questions and information that farmers want, the team can make the scheduled messages more relevant to the farmers.

Challenges remain

Challenges do remain. Identifying, tracking and addressing farmers’ information needs takes a lot more effort, money and time than a simpler ‘push’ delivery system, which raises the question of whether such an approach is sustainable in the long-term. Ultimately, the real test of the project’s success is whether farmers find the service worth paying for.

Early results are promising. Satish Singh, a 36-year-old farmer from Haryana, who grows rice, wheat and maize, says, “The information on insecticides and pesticides has been very useful. I have got recommendations on how to prevent certain diseases on paddy crop. The messages on crop residue management are informative too.” He feels that the messages could also include information on vegetables and government schemes. Asked if he would pay for the service, he said, “Yes, I think I would pay up to 500 rupees [about USD 8] for a six-month period.”

Further reading on the same topic:

- BLOG: Cell phones connect farmers to a food secure future

- BLOG: What's needed to help smallholders make better use of climate information?

- BLOG: Providing climate services that make sense to farmers

Surabhi Mittal is a Senior Scientist, Information, Markets & Policy, at CIMMYT, India. Dharini Parthasarathy is a Communications Specialist at CCAFS South Asia. Paul Neate, freelance science writer, edited the story