Fisheries

- Fishery adaptation strategies will vary considerably across the globe—from changing locations to shifting the timing and species targeted—depending on the local impacts of climate change (Cochrane et al. 2009; Grafton 2009).

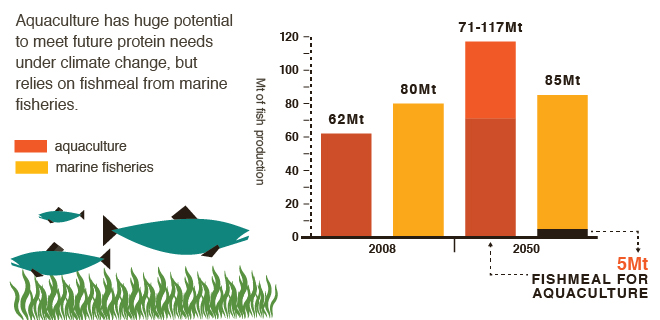

- There is huge potential to expand aquaculture (raising of fish in captivity in the sea or freshwater) even in the face of climate change (Cochrane et al. 2009).

- Aquatic species that do not migrate extensively and that have wide environmental tolerances can be used in aquaculture and targeted by capture fisheries to help adapt to new climatic conditions (FAO 2013 p. 93).

- Improving the general resilience of fisheries and aquaculture systems will reduce their vulnerability to climate change. For example, biodiversity-rich fisheries are less sensitive to climate change than those that are overfished and have little biodiversity. Healthy coral reef and mangroves systems, for example, provide natural barriers to physical impacts such as storm surges. Communities that are dependent on fisheries and aquaculture have strong social systems and a portfolio of livelihood options that have higher adaptive capacities and lower sensitivities to change. Larger-scale production systems that have effective governance systems and high capital mobility tend to be more resilient to change than smaller-scale systems or those with weak governance systems (De Young et al. 2012 p. 9).

- Technical innovation provides some adaptation options. Such innovations include: breeding aquaculture species that are tolerant of saline water to confront sea-level rise; development of storm-resistant fish farming systems (e.g. sturdier fish cages); and the widespread use of information technology to share weather and market information (De Young et al. 2012 p. 10).

- Governance of fisheries affects the range of adaptation options available and will need to be flexible enough to accommodate changes in stock distribution and abundance. Governance aimed at supporting equitable and sustainable fisheries, that accommodates inherent uncertainty and that is based on an ecosystem approach, as currently advocated, is thought to generally improve the adaptive capacity of fisheries (Daw et al. 2009 p. 108).

- Strategies that make the fishing system more sustainable and economically rewarding are essential to help small-scale fisheries adapt to climate change. Specific adaptation interventions should build on fishers’ current strategies for dealing with risk, shocks and change to avoid maladaptation. They should recognize places where climate change will benefit local fisheries as well as those places where climate change will have a negative impact (Badjeck et al. 2010).

- An effective means to build resilience of ocean systems would be to tackle other stressors such as pollution, overfishing and trawling that are already degrading ecosystems and exacerbating vulnerability to climate change (Nellemann et al. 2008).

Examples of measures to adapt to climate impacts on fisheries

| Impact on fisheries | Potential adaptation measures |

|---|---|

| Reduced fisheries productivity and yields |

Access higher-value markets Increase effort or fishing power* |

| Increased variability of yield |

Diversify livelihood portfolio Insurance schemes Precautionary management for resilient ecosystems Implementation of integrated and adaptive management |

| Change in distribution of fisheries |

Private research and development and investments in technologies to predict migration routes and availability of commercial fish stocks* Migration* |

| Reduced profitability |

Reduce costs to increase efficiency Diversify livelihoods Exit the fishery for other livelihoods/investments |

| Increased vulnerability of coastal, riparian and floodplain communities and infrastructure to flooding, sea level and surges |

Hard defences* Managed retreat/accommodation Rehabilitation and disaster response Integrated coastal management Infrastructure provision (e.g. protecting harbours and landing sites) Early warning systems and education Post-disaster recovery Assisted migration |

| Increased risks associated with fishing (e.g. safety at sea) |

Private insurance of capital equipment Adjustments in insurance markets Insurance underwriting Weather warning system Investment in improved vessel stability/safety Compensation for impacts |

| Trade and market shocks |

Diversification of markets and products Information services for anticipation of price and market shocks |

| Displacement of population leading to influx of new fishers |

Support for existing local management institutions |

| Various |

Publicly available research and development |

|

* Adaptations to declining/variable yields that directly risk exacerbating overexploitation of fisheries by increasing fishing pressure or impacting habitats Source: Based on De Young et al. (2012 p. 11). |

|

Examples of measures to adapt to climate impacts on aquaculture

| Impacts | Adaptive measures |

|---|---|

| Temperature rise above optimal range of tolerance |

Better feeds Selective breeding for higher temperature tolerance |

| Increased growth rates as a result of temperature change; higher production |

Increase feed input and better management |

| Eutrophication and upwelling; mortality of stock |

Better planning: farm/cage siting conforming to ecosystem carrying capacity Regular monitoring |

| Increased virulence of dormant pathogens |

None; monitoring to prevent health risks |

| Limitations on fishmeal and fish oil supplies/price |

Fishmeal and fish oil replacement New forms of feed management Shift to non-carnivorous species |

| Coral reef destruction |

None, but shifting from harvesting to breeding of coral reef species may improve reef resilience by reducing fishing pressure and harmful fishing practices |

| Saltwater intrusion |

Shift non-salt-tolerant species upstream (costly) Grow new salt-tolerant species in old facilities |

| Loss of agricultural land |

Promote aquaculture to provide alternative livelihoods Capacity building and infrastructure |

| Indirect influence on estuarine aquaculture through changes in brood stock and seed availability |

None |

| Impact on calcareous shell formation/deposition |

None |

| Limitations on water abstraction |

Improve efficacy of water usage Encourage non-consumptive water-use aquaculture, e.g. cage-based aquaculture and/or mariculture |

| Water retention period reduced |

Use of fast-growing fish species Increase efficacy of water sharing with primary users e.g. irrigation of rice paddy |

| Availability of wild seed stocks reduced/period changed |

Shift to artificially propagated seed (extra cost) |

| Destruction of facilities; loss of stock; loss of business; large-scale escapes with the potential to affect biodiversity |

Encourage uptake of individual/cluster insurance Improve design to minimize mass escape Encourage use of indigenous species to minimize impacts on biodiversity. |

| De Young et al. (2012 p. 11) after Cochrane et al. (2009). | |

- Badjeck MC, Allison EH, Halls AS, Dulvy NK. 2010. Impacts of climate variability and change on fishery-based livelihoods. Marine Policy 34:375–383. (Available from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2009.08.007)

- Cochrane K, De Young C, Soto D, Bahri T, eds. 2009. Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture: overview of current scientific knowledge. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper no. 530. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0994e/i0994e00.htm) (Accessed on 5 November 2013)

- De Young C, Soto D, Bahri T, Brown D. 2012. Building resilience for adaptation to climate change in the fisheries and aquaculture sector. In: Meybeck A, Lankoski J, Redfern S, Azzu N, Gitz V, eds. Building resilience for adaptation to climate change in the agriculture sector. Proceedings of a Joint FAO/OECD Workshop, 23–24 April 2012. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3084e/i3084e.pdf) (Accessed on 5 November 2013)

- Daw T, Adger WN, Brown K, Badjeck MC. 2009. Climate change and capture fisheries: potential impacts, adaptation and mitigation. In: Cochrane K, De Young C, Soto D, Bahri T, eds. 2009. Climate change implications for fisheries and aquaculture: overview of current scientific knowledge. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper no. 530. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/012/i0994e/i0994e00.htm)

- FAO. 2013. Climate-smart agriculture sourcebook. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3325e/i3325e.pdf) (Accessed on 5 November 2013)

- Grafton RQ. 2009. Adaptation to climate change in marine capture fisheries. Environmental Economics Research Hub Research Report No. 37. Canberra: Australian National University. (Available from http://www.crawford.anu.edu.au/research_units/eerh/ pdf/EERH_RR37.pdf) (Accessed on 5 November 2013)

- Nellemann C, Hain S, Alder J, eds. 2008. In dead water – merging of climate change with pollution, over-harvest and infestations in the world’s fishing grounds. Arendal, Norway: United Nations Environment Programme. (Available from http://www.unep.org/pdf/indeadwater_lr.pdf)