General Facts

Facts

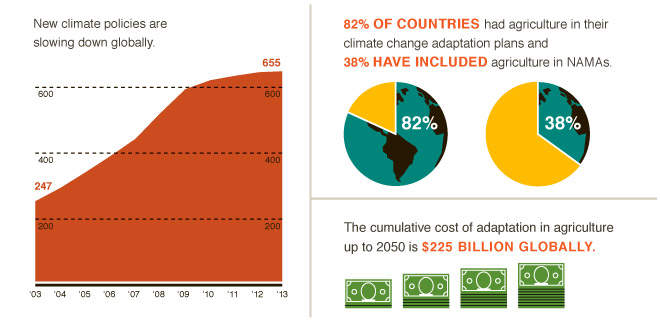

- Globally, fewer new climate policies are being introduced (Robins et al. 2013), but many countries are currently mainstreaming earlier climate change policies across sectoral programmes.

- The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has created several vehicles to help structure national policy and to deliver international public finance:

- National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) aim at identifying medium-term and long-term adaptation strategies. They are currently under development in many countries around the world.

- National Adaptation Programs of Action (NAPAs) are designed to help Least Developed Countries (LDC) identify priority activities that respond to their urgent and immediate needs to adapt to climate change. Many NAPAs include agriculture, food security, water resources and disaster management as priorities. The 50 countries that have submitted NAPAs to the UNFCCC secretariat are listed here.

- The Global Environment Facility (GEF), through the LDC Fund (LDCF), has financed the preparation of 50 NAPAs, of which 49 have been completed. Forty-seven countries have officially submitted NAPA implementation projects for approval by the LDCF/Special Climate Change Fund Council or the GEF Chief Executive Officer.

- Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) are sets of policies and actions that countries undertake towards their international commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There are 55 formal NAMA proposals, 21 of which propose actions in the agriculture sector. There are 62 agricultural mitigation plans in 30 countries, that is, plans not formally proposed as NAMAs (Wilkes et al. 2013).

- Countries have also introduced a range of policy vehicles to coordinate and mainstream climate policy and to include the UNFCCC elements. Government mechanisms include climate action plans, low emissions development plans and climate change adaptation plans.

- Some 82% of countries surveyed in 2011 had prioritized agriculture in their climate change adaptation plans (Action Aid, 2011).

- Twenty-one of the 55 countries that have submitted NAMAs to the UNFCCC have included actions on agriculture (Wilkes et al. 2013).

- Actions included in agricultural NAMAs centre on production and on environmental management, specifically:

- Crop-residue management;

- cropland-related mitigation practices in specific areas;

- restoration of grasslands and degraded agricultural lands;

- fodder-crop production;

- introduction of combined irrigation and fertilization techniques to increase efficiency;

- improved productivity of livestock; and

- reduced forest conversion and plantation of forests on agricultural land (Wilkes et al. 2013).

- Commitment to reduction of hunger and malnutrition is highly variable across countries. Countries with a high commitment include Brazil, Guatemala, Indonesia, Madagascar and Malawi (HANCI 2013). An increasing number of countries, currently 43, have joined the Scaling Up Nutrition movement, which is working towards providing all people with good food and nutrition (SUN 2013). The complete list of countries can be seen here.

- Food-security policies increasingly recognize climate change as a major threat to food and nutritional security, and governments are seeking to address the linkages via support to climate-smart agriculture, defined as “agriculture that sustainably increases productivity, resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes greenhouse gases (mitigation), and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals” (FAO 2010), and supply chain interventions and social protection systems.

- Total costs for adaptation in agriculture have been estimated at USD 7 billion per year up to 2050 (Nelson et al. 2009), USD 11.3–12.6 billion per year in the year 2030 (Wheeler and Tiffin 2009) and a cumulative USD 225 billion up to 2050 (Lobell et al. 2013).

- Total flows of climate finance across all sectors were approximately USD 364 billion in 2011. Of this, about 26% was public sector funding (domestic, bilateral and multilateral) and 74% private sector finance. All the private sector finance and a majority of the public sector finance was directed at mitigation; mitigation activities received about 95% of all climate financing, the remaining 5% going to adaptation activities (Buchner et al. 2012). There are considerable opportunities for co-benefits between mitigation and adaptation, so there is not in fact a “hard boundary” between the two uses of climate funds.

- The total investment by governments and development finance institutions in mitigation amounted to USD 80.4–83.7 billion in 2011, of which less than 5% went to agriculture, forestry and land-use interventions (Buchner et al. 2012).

- In 2011, the majority of registered agriculture, forestry and land use (AFOLU) projects in the carbon market related to pig manure, although reforestation projects are the second most numerous category. Africa has seen a large increase (20%) in relative terms in AFOLU mitigation projects from 2010 to 2011 (FAO 2013a).

- About USD 11.8 billion per year goes to interventions aimed at reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) (Buchner et al. 2012).

- Adaptation finance is more difficult to quantify than mitigation finance, since there is little agreement on what constitutes an adaptation action or additionality, i.e. the requirement that the greenhouse gas emissions after implementation of a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project activity are lower than they would have been under the most plausible alternative scenario to the implementation of the CDM project activity. As a rough estimate, out of the approximately USD 16.3 billion invested by governments and development finance institutions in adaptation, 27% (USD 4.4 billion) went to AFOLU. Note that these figures on public adaptation finance exclude a further USD 352 million that comes from Climate Funds’ adaptation financing and the estimated USD 120 million of philanthropic contributions targeting adaptation (Buchner et al. 2012).

- The major source of finance for adaptation in agriculture is multi-lateral financial institutions, which invested USD 2.6 billion in adaptation in the agriculture and forestry sectors in 2011. National financial institutions and sub-regional development banks invested USD 1.6 billion (Buchner et al. 2012). This figure does not include the new Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Program of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, which, as of July 2013, had received USD 330 million in pledges to support adaptation among smallholder farmers vulnerable to climate change.

Sources and further reading

- ActionAid. 2011. On the brink: who’s best prepared for a climate and hunger crisis? Johannesburg. (Available from http://www. actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/scorecard_without_embargoe.pdf) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- Buchner B, Falconer A, Hervé-Mignucci M, Trabacchi C. 2012. The landscape of climate finance 2012. San Francisco, CA, USA: Climate Policy Initiative. (Available from http://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/The-Landscape-of-Climate-Finance-2012.pdf)

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2010. “Climate-smart” agriculture: Policies, practices and financing for food security, adaptation and mitigation. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1881e/i1881e00.htm) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013a. Agriculture, forestry and other land use mitigation project database: Second assessment of the current status of land-based sectors in the carbon markets. Mitigation of Climate Change in Agriculture Series 6. Rome. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3176e/i3176e.pdf) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013b. Module 13: Mainstreaming climate-smart agriculture into national policies and programmes. In: FAO. Climate-smart agriculture sourcebook. Rome. (Available from http://www.fao.org/climatechange/climatesmart/en/) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- [FAO] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013c. Module 14: Financing climate-smart agriculture. In: FAO. Climate-smart agriculture sourcebook. Rome. (Available from http://www.fao.org/climatechange/climatesmart/en/) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- [HANCI] Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index. 2013. Hunger and Nutrition Commitment Index [homepage]. http://www.hancindex.org (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- Lobell DB, Baldos ULC, Hertel TW. 2013. Climate adaptation as mitigation: the case of agricultural investments. Environmental Research Letters 8: 015012 doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/015012.

- Nelson GC, Rosegrant MW, Koo J, Robertson R, Sulser T, Zhu T, Ringler C, Msangi S, Palazzo A, Batka M, Magalhaes M, Valmonte-Santos R, Ewing M, Lee D. 2009. Climate change. Impact on agriculture and costs of adaptation. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute. (Available from http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/pr21.pdf)

- Robins N, Knight Z, Wai-Shin Chan, Singh C. 2013. Peak planet: the next upswing for the climate agenda. HSBC Global Research. Hong Kong: Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited.

- Streck C, Burns D, Guimaraes L. 2012. Towards policies for climate change mitigation: Incentives and benefits for smallholder farmers. Report 7. Copenhagen, Denmark: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security. (Available from http://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/21114) (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- [SUN] Scaling Up Nutrition. 2013. Scaling Up Nutrition [homepage]. http://scalingupnutrition.org/ (Accessed on 13 November 2013)

- Wheeler T, Tiffin R. 2009. Costs of adaptation in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. In: Parry M, Arnell N, Berry P, Dodman D, Fankhauser S, Hope C, Kovats S, Nicholls R, Satterthwaite D, Tiffin R, Wheeler T. Assessing the costs of adaptation to climate change: A review of the UNFCCC and other recent estimates. London: International Institute for Environment and Development and the Grantham Institute for Climate Change. pp. 29–39. (Available from http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/11501IIED.pdf)

- Wilkes A, Tennigkeit T, Solymosi K. 2013. National integrated mitigation planning in agriculture: a review paper. Mitigation of Climate Change in Agriculture Series 7. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (Available from http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3237e/i3237e.pdf)