New skills or access to resources: what do young farmers need most?

As the world celebrates Youth Skills Day today, we’ve been thinking about what skills young farmers need to adopt climate-smart practices on their farms.

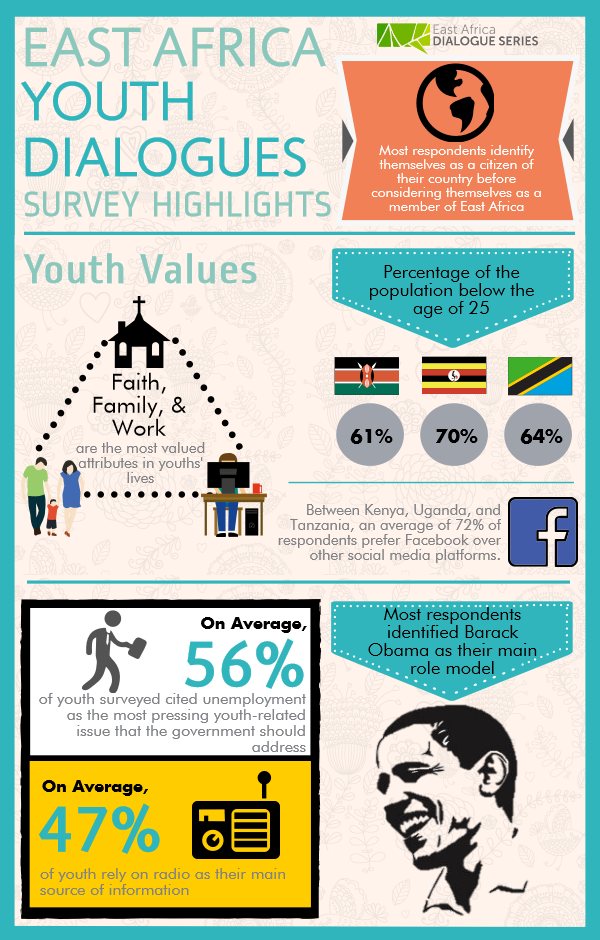

East Africa is currently experiencing a “youth bulge,” while Africa as a whole is widely cited as the youngest continent in the world. In 2010, 70% of the population in East Africa was under the age of 30 (UNECA and UN Programme on Youth). Not only do youth represent over half of the population, but, particularly in urban areas, this young group is also better-educated and more tech-savvy than ever before. The pervasive rhetoric in this region has been centered on the problem of youth unemployment, however, given other barriers such as climate change, limited land availability, and the assumption that university-educated youth all desire “white collar” jobs, what is the role of youth in agriculture moving forward?

As part of our ongoing research project, Youth Decision Making in Agricultural Climate Change Adaptation, we are exploring the extent to which youth have farming as their primary, if not sole, economic activity. In partnership with the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), our interest as researchers extends beyond climate change, farming practices, and climate smart agriculture (CSA), to the voice and duties of the youth that exist within these components.

Survey highlights from the East Africa Youth Dialogue. Infographic: East Africa Dialogue Series. [Source]

Our study is focused in the East African region, specifically the CCAFS research sites of Wote, Kenya, Lushoto, Tanzania, and Hoima, Uganda. At each site, through a series of focus group discussions and case study interviews with young locals between the ages of 18-35, we have been able to gauge the extent to which youth understand how to adapt to the climate-related changes impacting their agricultural practices, as well as the scope in which they are included in decision making at household and community levels.

Participants of a young women’s focus group discussion in Lushoto Tanzania, June 2016. Photo: C. Hein (University of Arizona).

What are the components necessary for youth to be empowered to make informed, beneficial decisions in regards to climate change adaptations in their farming practices? We have found that they already have the most important one: education. Although perhaps not a surprising conclusion, it was clear that the youth at the aforementioned sites have been exposed to various educational training opportunities promoting CSA, from CCAFS, other researchers, and government employees, particularly extension officers.

At all three sites, the youth displayed detailed understanding of weather patterns and how those have changed over the past ten years, as well as how these changes impact their agriculture practices. The youth were able to cite specific adaptations they had made to improve their agriculture practices, and the resulting improvements to their standard of living, such as having an increase in income and being able to invest in improved housing and transportation.

Participants in a young men’s focus group discussion in Hoima, Uganda, June 2016. Photo: G. Klasek (University of Arizona).

Although these educational successes could be attributed to the involvement of researchers in these areas over several years, there is no doubt that these youth, both men and women, are well versed in and already practicing CSA techniques, such as contouring, terracing, shade cropping, crop diversification, and use of fertilizers and improved seed varieties, among others.

The more access youth had to such educational opportunities, the more they reported decision making power in their households. Knowledge, rather than age, gender, or land ownership, was the primary factor in who had input in decision making in agricultural adaptations to climate change - at both the household and community level.

This conclusion reveals that the barrier to youth moving forward or improving their livelihoods in agriculture was not a lack of knowledge or training, but rather, a lack of access to inputs, which (depending on the site), include; fertilizer, improved seeds, access to loans and capital, and improvements to infrastructure. This infrastructure calls for improved roads, irrigation, and markets - both physical and economic.

The young farmers at these sites have the knowledge and trainings necessary to achieve success. It is already working. Now, the next step is required. The youth involvement in decision making at this junction is not a stifled youth voice, or lack of education, but rather, the inputs and resources necessary in their surrounding environments that can further empower them to use their voice and education to improve not only their own opportunities, but those of the family and community.

What’s next?

The current belief in East Africa is that perhaps the 30 million youth, who make up 40% of the employed and 60% of the unemployed in the region (East Africa Dialogue Series), can participate in agribusiness, as long as there is an increase in the availability of the necessary inputs to foster a successful agribusiness. Asserting that youth are more educated than ever before and thinking of that as an obstacle for promoting entrance into agriculture is shortsighted. In fact, youth are in a position to be more successful than any previous generation because of their education. The obstacle lies in the lack of availability of necessary inputs for youth to pursue agriculture as a successful, interesting, viable opportunity.

What do you think? Join in on the conversation for Youth Skills Day: CSA and Youth Engagement in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Read more...

Regional Overview: Youth in Africa. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa & The United Nations Programme on Youth. (2011).

East Africa Dialogue Series. Aga Khan University. (March 2015).

Kelly Amsler, Chloe Hein and Genêt Klasek are Masters in Development Practice candidates at the University of Arizona, in Tucson, Arizona. For questions regarding this project please contact k.amsler@cgiar.org, c.hein@cgiar.org and g.klasek@cgiar.org.