Climate change and social networks in Senegal's peanut basin

Researchers investigated the impact of climate change on small communities in Senegal’s peanut basin, exploring how empowerment in terms of the strength of social connections intersects with the use of climate information for agricultural management.

What do social networks have to do with climate change? Partners of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) from the University of Florida conducted a research project in Senegal’s peanut basin to continue investigating the impact of climate change on small communities and to explore how empowerment is conceptualized in these burdened communities. Preliminary findings show that strong social networks can help empower individual agriculturalists to adapt to climate change.

The project also served as an opportunity to follow-up on the climate forecast communication program initiated by CCAFS and partners to help farmers prepare for unpredictable weather and climate events.

Senegal's peanut basin

Kaffrine is a semi-arid department located in the center of Senegal, making up a large portion of Senegal’s peanut basin. Agricultural communities in the area primarily produce peanuts, millet, and cowpeas for domestic consumption and commercial profit. Other crops produced include sorghum, okra, and tomatoes.

The area has experienced significant climate-related shocks in recent years, including wind storms, drought, flooding rains, and unseasonable temperature changes—all of which create obstacles to maintaining agricultural production sufficient for livelihood security.

For this project, researchers from the University of Florida, working in partnership with the CCAFS Theme on Climate Risk Management, held focus groups in two communities, Kahi and Malem Thierign, on the topics of climate smart agricultural practices and empowerment.

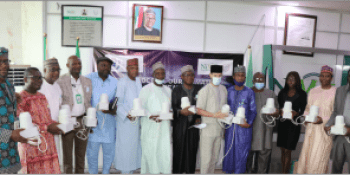

Kaffrine, in the heart of senegal's peanut basin, is home to a CCAFS climate smart village site. PHoto: Joseph Hill.

The focus groups gave community members the opportunity to share their experiences, thoughts, and insights on the strain that climate change has placed on their agricultural practices and how they are responding. Each of four focus groups, divided by age and gender, also shared their definitions and cultural perspectives of empowerment of both men and women. Understanding the various ways that empowerment is conceptualized and valued is essential to all future efforts within the communities to meet the challenges of climate change.

A changing climate

The focus groups created an opportunity for community discussions about the effects of climate change on crop production. Community members expressed significant concern over the strong winds that had destroyed millet and peanut crops in the recent past.

The lack of consistent rains during the rainy season – often accompanied by severe rains – was noted as another contributor to hardship. Farmers described peanut harvests of recent years where, despite crops growing to maturity, there were no groundnuts inside the shells. Such harvest deficits pose threats to both economic stability and food security for these communities.

Social networks, the crux of empowerment

Empowerment is often defined by a Western notion of individualism, but this is not how communities and cultures define empowerment the world over. Empowerment becomes particularly important in the context of agricultural production and climate change, where being able to adjust one’s livelihood requires one to be able to access resources in ways appropriate to cultural values and societal constraints, whatever those might be in any particular context.

To many, empowerment means the ability for one to be autonomous, and independent. While community members explained that they do define empowerment as consisting of a certain level of autonomy. Their descriptions of how one builds and maintains empowerment differs from common western, academic definitions of the term.

Preliminary findings indicate that empowerment in the context of Kaffrine is constructed heavily upon individuals being embedded in strong social networks – social networks on which individuals can rely in times of need or when putting forth effort to better one’s own circumstance. This key aspect of empowerment was identified by both men and women, and for both men and women.

For these two communities in Kaffrine, the ability to gain or improve one’s own empowerment rests heavily upon an individual’s ties to family, through blood relatives and through marriage, and their ability to benefit from assistance from members of this network, with emphasis on parents, spouses, and children.

Climate forecast provision and tying it all together

Understanding the importance of social networks to empowerment is crucial to developing effective interventions in climate change. The climate forecast communication program initiated by CCAFS and partners relies on communication through these social networks. Preliminary findings showed that individuals who did not have strong social networks did not receive weather information.

These individuals who do not receive weather and climate information therefore could not take proactive steps to alleviate negative impacts of climate change, thereby limiting their levels of empowerment with regards to their livelihood and exacerbating cycles of disempowerment. Such situations are illustrative of the description of empowerment that community members had described in focus group discussions. Social networks empower individual agriculturalists to adapt to climate change.

Sarah McKune is director of Public Health Programs at the University of Florida.

Thérése D'Auria Ryley is a doctoral student in medical anthropology at the University of Florida.