Kenya: A glimpse of climate-smart agriculture

There are many ways to describe Maurice Kwadha: farmer, entrepreneur, and climate-smart are some of them.

But some in Kombewa, in western Kenya’s Nyando Basin, used to call him a madman. Once, when he was collecting discarded milk packets at the local market, he was physically attacked by someone who thought he had lost his mind. But Maurice had a plan. And his small farm, with its burgeoning tree nursery, is the proof.

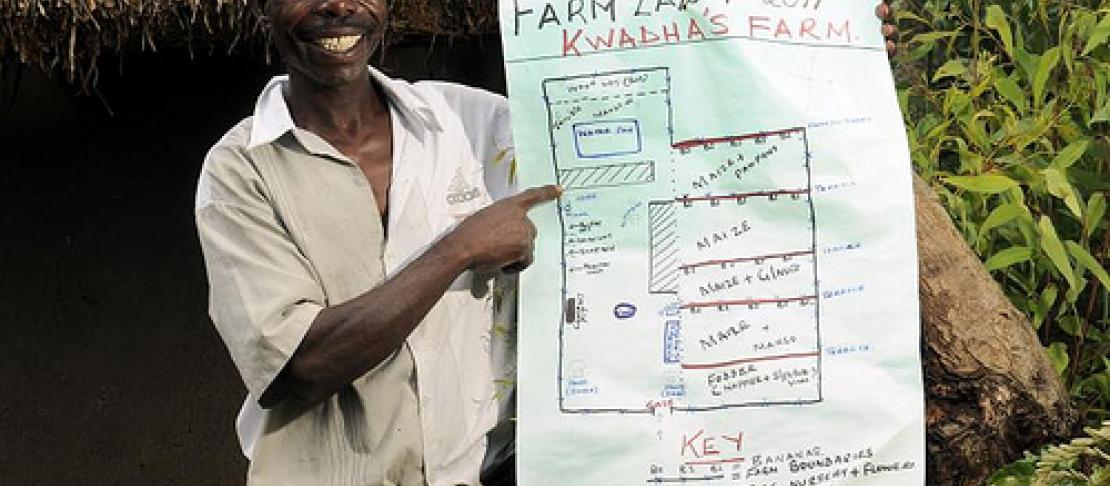

Standing in the afternoon sun at his farm in Kochiel village, he’s full of smiles. The day before he hosted a special event for World Food Day – which saw over 100 people, including the area’s provincial commissioner – take a tour of his farm. Even though Maurice has less than half-a-hectare of land, what he’s done with it is nothing short of inspiring, and is perhaps one of the best examples of climate-smart, sustainable, agricultural intensification in the region, if not the country. It’s little wonder it’s starting to get attention.

His agroforestry system has been established at just the right time, as the Nyando Basin, and many parts of East Africa, struggle to deal with increasingly unpredictable rains, and more intense dry spells. It shows that with a bit of lateral thinking, a small plot of land is no barrier to boosting food production, increasing resilience to climate change, and developing a profitable business.

In an area barely larger than a tennis court, he has dense, leafy plots in all shades of green. Areas of maize and the bushy fodder grass napier sit next to rows of banana and high-value papaya trees; several alleys of multi-purpose border trees including calliandra and grevillea help to stabilize and replenish the soil, maintain soil water, protect the topsoil from wind erosion, provide shade and fodder, and eventually fuel-wood and building material. He uses leaf mulch from tithonia plants as green manure for his fruit trees; further up he has a small area for onion, sweet potato and tomato.

His next-door neighbour’s farm, sown almost entirely to maize, seems horribly exposed in comparison. While heavy wads of mud cling to my shoes as we walk along the border of Maurice’s farm, the soil over the fence is dusty and dry. Maurice likens soil-use to having a bank account: you can’t keep withdrawing indefinitely if you have nothing saved up. At the moment, it looks as though his neighbour is in the red.

Maurice also has a unit for a dairy goat and hopes to establish a zero-grazing unit for his dairy cow. He’s also hand dug a large pond, fed by water pumped from a nearby seasonal river, installed an EcoSan toilet, and has a 3000 litre tank to capture rainwater from the tin roof of his home. Furthermore, he’s a committed composter, with various systems in place, and even has an ultra-efficient “rocket stove” for cooking.

“The mother of everything”

What Maurice is most proud of is his growing tree nursery, which despite being less than a quarter of the size of his cropland, is by far his most profitable enterprise. Here there are a whopping 20,000 seedlings of mango, calliandra, grevillea and local tree species. Some are for his farm, but the majority are for sale.

Many of the seedlings are growing in the discarded plastic bags used for milk, the same ones that caused Maurice to attract the wrong kind of attention as he picked them up off the floor at his local market. He says that recalling the incident still brings tears to his eyes. In farming, sometimes you have to act like a person who is mad, he explains. But as long as you know what you’re doing, you’ll be okay.

As well as collecting old milk packets, Maurice also picked up discarded mango seeds to establish his mango nursery. He now sells seedlings to a variety of customers, including the Kenyan government. He’s also started grafting mango.

The money from the tree nursery enabled Maurice to buy and install his water harvesting tank. His water pump was also bought with money from the nursery. Water pipes too. And his television. Money from the tree nursery enables him to send one of his children to school and another to college.

If we want to talk more about what he has bought with money from the tree nursery, we‘ll be here until evening-time, he chuckles. With a sweep of his hand, he says simply, that the tree nursery “is the mother of everything here.”

Despite this, Maurice concedes that for one person alone, environmental conservation is not easy – networking and collaboration are essential – and he admits there is still a long way to go. But he believes that if the whole community can see what he is doing, and adopts similar practices, together there will be a significant change for the better. His involvement as chairman of the the a local youth group, is one step towards this.

“What I’ve learned in farming here is, however small it is, what matters is the way you utilise your farm.”

Now, whichever words the the local community uses to describe Maurice, mad is definitely not one of them.

In July 2011, Maurice helped to coordinate the first of a series of workshops with the CGIAR’s Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) research program, with partners from the University of Oxford. The workshops aim to improve the capacity of rural communities to address their most pressing challenges. More on this coming soon. Kochiel is also one of several villages participating in Africa’s first soil carbon project operated by Swedish NGO SCC-ViAgroforestry (ViA) together with the World Bank and the Kenyan government.

This post written by Neil Palmer, of the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), and originally published on the CIAT blog. The post contributes to Blog Action Day 2011, which coincides with World Food Day.