Feast or famine: A tale of two agricultural cities

Spooner, Wisconsin is sleepy little town in the heartland of the United States. It is home to around 2,500 weather-hardened northerners living near the frigid border of Canada on the northernmost reaches of the nation’s corn belt. The town’s motto is “Crossroads of the North” given the two major highways that intersect in the heart of Spooner. For the six months of the year that the landscape isn’t covered in snow, this two-stoplight town is nestled in a visible patchwork of cropland and pasture. Spooner is a place I'm proud to call my hometown.

Wisconsin is a state rich in agricultural tradition. The nickname “America’s Dairyland” is proudly maintained among Wisconsinites, reflecting the state’s long history in cheese and milk production. Agriculture is a USD $60 Billion industry in this state of just over 5 million people. The sector provides jobs for about 10% of Wisconsinites, including some 78,000 farms, as well as processing, horticulture, and the forestry and logging industries.

A world apart

Orbili Ghana, some 9,000 km east of Spooner, lies in the Guinea Savannah Zone, just below the driest reaches of the vast Sahara desert in Africa. Orbili is the site of CCAFS Systemic Integrated Adaptation (SIA) research project. Lawra, the capital city of the district in which Orbili is located, is home to about 6,000 people and serves as a crossroads in its own right – this time between Ghana and neighboring Burkina Faso.

Orbili too is an agricultural community within an agricultural state. The sector accounts for about 80% of the district economic production, and employs about 83% of the population. Ghana as a whole produces an agricultural GDP of approximately USD $18.76 Billion (or 22.7% of total GDP) in a country of 25 million people.

While worlds apart by most metrics, Spooner faces similar challenges to that of Orbili; a young generation losing interest in farming, migration towards larger urban centers, and most pertinent here, changing climates.

In Wisconsin, April 2013 was among the wettest on record, and July among the driest. Extreme flood and drought events are expected to continue across the state, as is a rise in mean temperatures. Similarly, Ghana has seen an increase in average temperatures of 1°C over the past 30 years according to the country’s most recent United Nation’s framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) national communication.

Some estimates in the same report suggest temperatures in the country’s northern savannah zone to increase between 1.7°C and 2.4°C by the year 2030. Extreme weather events like torrential rains, excessive heat and extreme dry winds already plague the region.

The principle difference between Spooner and Orbili is that when climate impacts occur agricultural producers in Wisconsin (and in the United States more generally) have the resources and institutions to cope and adapt to ensure food security. When a subsistence producer, like the majority of those farmers in Orbili, experiences the same magnitude impact it is quite literally a matter of life and death.

It may seem bizarre to be comparing two communities so distant from one another in terms of economic development, culture, and geography. But that is just the point. Different political-economic realities call for different adaptation responses. It would be misleading to assume that if only Ghana could adopt similar practices to that of Wisconsin that they too could improve their climate resilience. Truth be told, some practices are not worthy of transfer.

A model of resilience?

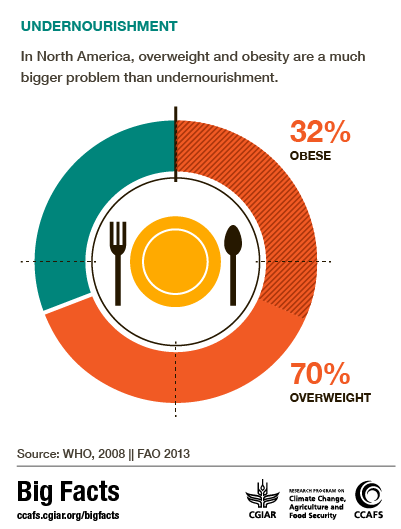

As indicated by a recent CCAFS blogpost highlighting “Big Facts” on North American agriculture, overconsumption is the principle food security threat facing the United States. More than two-thirds of all American adults are overweight.

United States. More than two-thirds of all American adults are overweight.

Equally troubling is that total avoidable food waste in the United States is estimated to be 55 million tons per year for 2009, which amounts to 28.7% of total annual production by weight (Venkat 2011). The ample availability of grain storage facilities and efficient systems of market access ultimately contribute little to adaptive capacity when consumption patterns remain as egregious as they currently do.

Similarly, the privatization of agriculture --a major development priority for emerging economies like Ghana -- is no panacea for reducing climatic risk.

Private interests in the agricultural sector in the United States have led to substantial losses in crop diversity through extensive monocultivation of maize and soya. The nation faces a profound need to diversify crop production, or at the very least maintain diversity in staple crop varieties.

Crop insurance is another widely discussed adaptation measure applied in both developed and emerging economies alike. The most recent Farm Bill voted through the United States Senate on February 4th of this year (valued at one trillion dollars -- that's trillion with a ‘t’) moves the country towards a crop-insurance model that compensates farmers in the event of crop loss or commodity price fluctuations. Yet early experiences with the federally subsidized private crop insurance point to questionable outcomes. In 2012, despite widespread drought across the country, U.S. farmers logged record profits. This is because federally insurance subsidies were paid out to farmers at the inflated prices caused by the production shortages.

‘Private’ agricultural production in the United States is hugely subsidized by taxpayers and can encourage dangerous risk taking and agricultural expansion. Since 1995, Washburn County, where Spooner is located, has received USD $5.79 million dollars in crop insurance subsidies, and USD $11.3 million in commodity (corn) subsidies.

Most of this spending is put good use by those in need given that Wisconsin still maintains a strong network of small farms. But this isn't always the case. Federal subsidies have been shown to dispraporitionally benefit wealthy commercial agricultural enterprises (see this Bloomberg article). Ironically, it may be that the same robust state and federal institutions providing safety nets against climate risks that pose the greatest threat to food security in the United States.

Strong adaptive institutions and infrastructure, private sector engagement, crop insurance, and a certain amount of risk taking all have a role to play in contributing to the improved adaptive capacity of small-scale farmers in Ghana. But we should use caution in transfering these measures blindly from one context to another upon the false assumption that developed country agricultural sectors are models of resilience worth striving towards. In this instance there are equally valuable lessons to be learned from both sides of the pond.

HAVE YOUR SAY

What lessons can industrialized nations take from agricultural practices in places like Oribili, Ghana that may lead to improved resilience and adaptive capacity? Leave your ideas in the comments section below!

Read more about the Systemic Integrated Adaptation (SIA) project.

Chase Sova is a visiting researcher at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT), a member of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), and a doctoral candidate at the University of Oxford, Environmental Change Institute (ECI). He works with CCAFS Theme 1: Adaptation to Progressive Climate Change.