The house made from apples

This post was first published on the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) blog by Neil Palmer.

There are no apples on the trees in Burva village at this time of the year, but the impact of apples is everywhere.

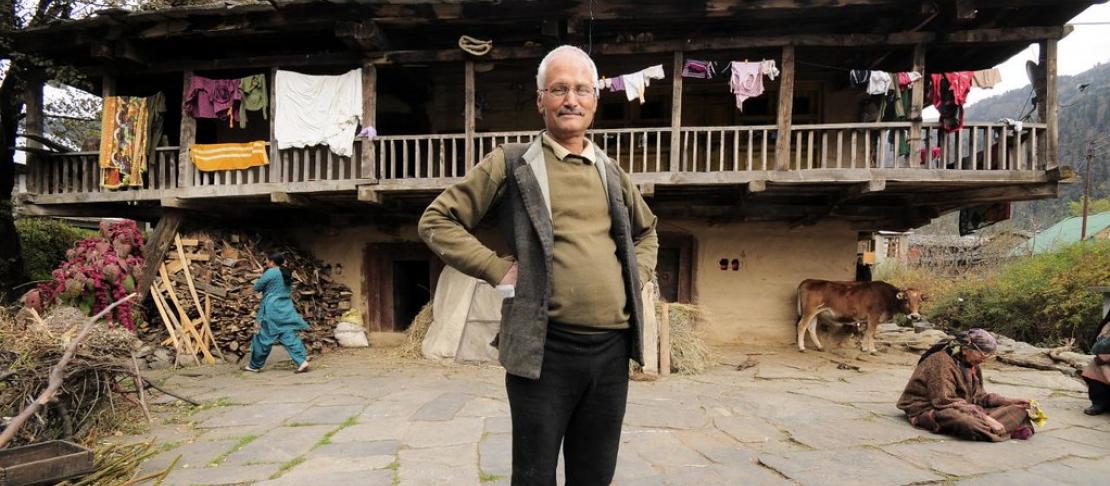

Take 58-year-old Balakram Thakur. He was born and raised in this, a traditional two-storey house made from wood, mud and stone.

Now he lives here – literally the next house across the road – in a three storey brick abode with no fewer than 13 rooms. There are two cars in the driveway, and a tractor.

He attributes everything to apples.

Apple rush

Burva, in the shadow of the snowy Hamta Pass, some 2000m above sea level in India’s Himachal Pradesh, is in the state’s new apple zone.

For years apples were grown some 60 kilometres away, and several hundred metres downhill, in and around the town of Kullu. But rising temperatures began eating into apple yields and affecting quality. Gradually the apple belt was pushed to higher, cooler ground.

Over time, farmers like Thakur switched from traditional subsistence crops like wheat and maize, and apple blossomed.

Now apple is the village’s primary cash crop, and growers no longer need to travel to nearby towns in search of middlemen to buy their Royal Delicious varieties; the middlemen now come to Burva. Thakur himself sells all the apples from his 400-or-so trees from his driveway.

Villagers outside the local grocery shop tell us that around 80 per cent of the inhabitants of Burva now grow apples. The crop has enabled many to own either cars or motorbikes, and mobile phones. They can also afford to send their children to good schools.

Climate-smart to the core

For the farmers of Burva, climate change has brought new, profitable opportunities, and central to their success has been their willingness and ability to respond effectively to the new conditions. A lucrative apple market, together with government subsidies for inputs like fungicide, and technical advice from scientists, certainly oiled the wheels of adaptation.

Not content to rest on his laurels, Thakur is already looking to the future, and investigating ways of improving and diversifying his farm. He’s building an apiary to aid apple pollination next season, has planted some recently-developed early-maturing apple varieties, and is thinking about planting another lucrative fruit – pomegranate.

He also lets us sample this year’s high-value walnuts and hazelnuts. While I need to bash the hazelnut shell with a stone, he cracks it between his teeth, and breaks the walnut shell in the palm of his hand. “I’m not just a farmer,” he says, “I’m a hard worker. I can lift one quintal,” he tells us.

So it’s no surprise when he also tells us he built this modern, apple-funded 13-room home himself. But what we didn’t expect was that it’s not the only house he has made from apples. He has not just one, but two more nearby.

And what about the farmers downhill in Kullu? Well, they’ve also shown that they can be climate-smart, by proving that there can be life-after-apples. More on that soon.