An investment case for reducing livestock emission intensities in East Africa

Expected population growth and increasing consumption of dairy and meat are driving demand for climate-smart livestock production in East Africa.

Livestock—key to livelihoods and food and nutrition security for millions—is responsible for 40% of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from agriculture. And emissions are increasing year upon year, as production increases. One way to bend the curve of emissions is to reduce the emission intensity of dairy and meat, which means producing the same amount of dairy or meat with fewer emissions.

Reducing emission intensity is especially important for countries like Ethiopia and Kenya, where the livestock sector accounts for 12% and 25% of gross domestic product (GDP), respectively, and current livestock production is emission-intensive. As both Ethiopia and Kenya raised livestock as a component of their Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to global climate change mitigation, the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS)—with its partner the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)—recently published reports on the feasibility of various low-emission livestock options in the countries and an investment case for one LED option.

Options exist, but are they feasible?

ILRI researchers Polly Ericksen and Todd Crane examined nine feed quality and availability, manure management, and animal husbandry measures that could reduce the emission intensity of livestock in East Africa for their technical potential, their suitability for specific farming systems in East Africa, and barriers to adoption and potential incentives for East African livestock farmers.

Read the report: |

Researchers found multiple options with high technical mitigation potential, for example:

- Producing and using improved forage for animal feed could reduce emission intensity by 8–24% on intensive and semi-intensive dairy farms in Kenya, and up to 27% in mixed systems in Ethiopia.

- Biodigesters in intensive dairy farms with four to five cows or more could cut total emissions from manure by 60–80%.

- Improving manure storage and covering could reduce methane emissions from manure by up to 90%.

- Reducing the chronic disease burden increases productivity and decreases emission intensity across systems, though the rates of improvement depend on disease targeted.

- Reducing the age at which meat animals are slaughtered while improving feed quality reduce the emission intensity of cattle by 40% and of sheep and goats by 34% in extensive pastoral systems.

Addressing costs, barriers and incentives could pay off for both the environment and farmers, researchers said

Though the options listed above have high technical mitigation potential, adoption is hampered by widely varying suitability; barriers such as initial cost and poor information available to farmers and extension services; and a lack of public and private sector incentives to catalyze change.

Also, women tend to face additional barriers to changing practices due to lack of ownership rights, decision-making power, and a host of other factors. These gender issues are not isolated to East Africa or dairy systems, however, as evidenced by a sustainable development goal, and a CGIAR-wide focus, on gender.

Is there a business case?

Kenya’s government certainly thinks so. Kenya’s Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions for the dairy sector (2017) include increased commercial production of fodder, accomplished partly through extension services focused on productivity.

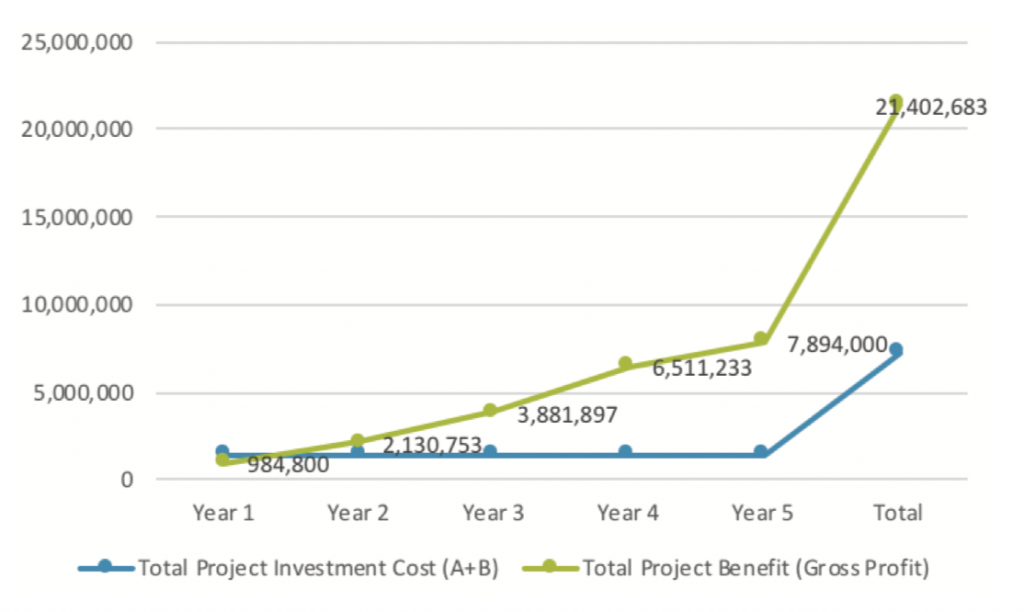

In a 2018 cost–benefit analysis of fodder production as a low emissions development strategy for the Kenyan dairy sector, researchers found that a public investment in a program for 30,000 smallholder households over a five-year period would cost USD 3.3 million. By the second year, the value of productivity would be more than project costs. After five years, total project benefits would be valued at three times the project cost.

Source: Kashangaki & Ericksen 2018

Critical to the success of improving fodder is the involvement of non-farm actors, in particular extension services and dairy cooperatives/producer organizations, researchers said. Both of these services provide information and access to seeds and other inputs that would be necessary for expanded and improved fodder production. In addition, cooperatives could support farmers by helping with access to finance and more stable markets, and returns for fodder production.

Read the report: |

Reductions in emission intensity vary based on levels of intensification, feed regime adoption, and number of animals. In 2017, scientists estimated that emission intensity could decrease by 8 to 24% in intensive and semi-intensive dairy systems in Kenya. A more spatially-explicit analysis in 2018 suggests that combining increased use of the most common improved forage—Napier grass—with dairy concentrates, could reduce emissions intensities in the Kenya dairy sector by 26 to 31%.

This business case digs into just one of the low-emission options identified for Kenya. But it is not the only one. If government and the private sector commit to developing policy and financial tools that improve productivity and reduce greenhouse emissions in the livestock sector, governments will meet global climate change mitigation goals, and investors and businesses—including farmers—will benefit from greater profitability.

Read More:

- Report: The feasibility of low emissions development interventions for the East African livestock sector: Lessons from Kenya and Ethiopia

- Report: Cost–benefit analysis of fodder production as a low emissions development strategy for the Kenyan dairy sector

- Blog: Investing in low emissions development strategies in the dairy sector: Viable options for Kenya and Ethiopia

- Article: Gender power in Kenyan dairy: Cows, commodities, and commercialization

- Webpage: Learn more about the CCAFS-USAID collaboration on low-emissions opportunities in agriculture and food security here.

Julianna White is Program Manager for CCAFS Low Emissions Development.