An eleven-step program: Roadmaps for measurement, reporting and verification of climate-smart agriculture

Setting out country-specific roadmaps to develop harmonized systems for monitoring and reporting on climate-smart agriculture.

New country-driven assessments on national monitoring and evaluation (M&E) of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) provide rich insights into the needs, systems and opportunities for tracking progress and impacts of CSA interventions.

The research, carried out with funding from Vuna by scientists at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), Unique Forestry and Land Use, and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), in collaboration with the governments of Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe, aimed to set out country-specific roadmaps for developing harmonized systems for monitoring and reporting on CSA.

Insights from Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe

The CSA measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) profiles used a country-driven approach to document stakeholders’ information needs, uses and capacities, exploring how to build on and align CSA M&E with existing M&E systems and international reporting frameworks. The scientists engaged more than 100 representatives of government institutions, development partners, NGOs, institutions of higher learning and research, and the private sector in the four countries. Here we share three key findings for the development of national M&E systems for CSA and similar targeted initiatives in developing countries (such as land restoration under the Bonn Challenge).

1. CSA M&E can fill critical information gaps. Stakeholders’ needs for and uses of M&E differ. Government ministries use M&E in policymaking, providing support or finance, planning, guiding implementation, and reporting. Donors, research institutes and NGOs use information for tracking progress and designing new interventions. Nearly everyone uses M&E to measure success. Yet, almost half of the stakeholders indicated that information is not readily available to meet their needs, which constrains their abilities to meet their policy, programming or reporting goals. Information gaps are found across various domains of the CSA-specific results framework, from inputs (e.g. budget allocated to CSA), activities (e.g. number of actors/institutions carrying out CSA activities), to outputs (farmers adopting CSA practices) and outcomes (impacts of CSA interventions on livelihoods and environmental indicators). Identifying and targeting these demand-driven gaps will help CSA M&E support multiple uses.

2. Indicators are only one essential component of CSA M&E. Aligning information flows across scales is necessary for maximizing efficiency and designing a shared pathway towards change. There are at least four levels at which CSA M&E plans need to be aligned:

- subnational (as local interventions usually come with their own M&E plans);

- national (e.g. programs and policies each having their own sets of indicators);

- regional (established reporting mechanisms such as the CAADP Results Framework); and

- international (e.g. communications to the UNFCCC).

There are many competing M&E frameworks within one country, setting up sometimes complementary and sometimes contradictory demands for time and resources. For instance, in Tanzania, the nearly 600 indicators used in different M&E systems illustrate significant overlaps, complementarities, and divergences among project, subnational and international systems. The abundance in frameworks reflects a rather disintegrated work on the emerging topic of CSA; different NGOs and donors have embedded their M&E needs into own systems, without necessarily linking them to existing governmental development frameworks. At the same time, it presents a major opportunity to create coherence among programs, so that the collected data can serve multiple purposes and reporting needs.

This abundance of frameworks and plans is partly explained by previously disintegrated work on the emerging topic of CSA, which has been more or less linked to existing government development frameworks and which has been promoted by different NGO and donor initiatives, each with their own M&E needs and systems.

3. Inadequate resource allocation has led to limited action on M&E of CSA; to push this forward, national capacity needs to be strengthened. The most significant constraints mentioned within existing M&E systems relate to inadequate budgets, outdated technology and a shortage of trained staff. M&E activities are often relatively poorly funded, which jeopardizes the quality of data because the amount of information requested often exceeds what is financially feasible. For instance, stakeholders in Zimbabwe noted that data collection procedures increase the likelihood of data quality problems, while Malawi’s Agriculture Sector Wide Approach M&E continues to use paper-based forms, slowing down the delivery of information and increasing chances of errors.

Throughout the region, capacity building should target both the front-line extension agents and others who collect field data, and also the back-end staff who compile and analyze information. Technical capacity must include acquiring software and computers needed to store and analyze data and data-literacy. Building multi-stakeholder platforms for sharing data and experience may help create institutional trust and collaboration. Investments in CSA M&E present an opportunity to reinforce and commit to institutional and human capacity in countries.

A roadmap towards coherent M&E of climate-smart agriculture

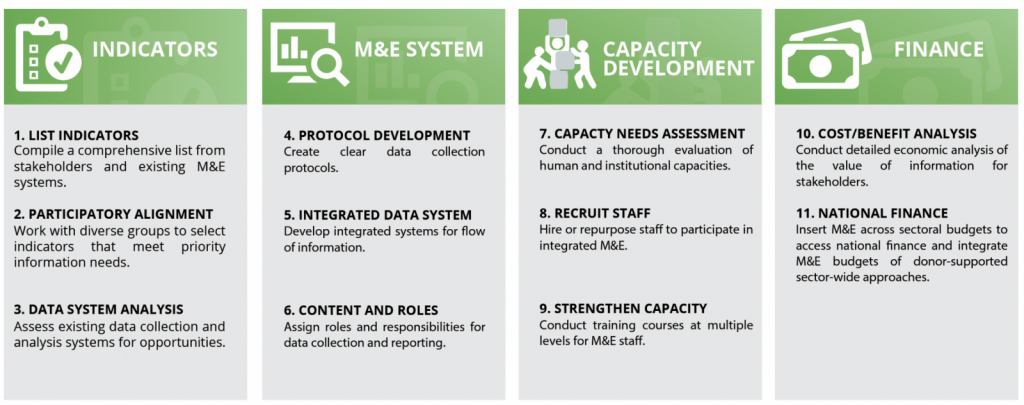

A general consensus across government ministries, development partners and NGOs in each country suggested that a national integrated system would provide a broad picture of national progress and fill critical institutional information needs. Looking across the four countries, 11 steps emerged for developing an internally consistent MRV system that could also be aligned with regional and international reporting requirements. In short, these steps will create effective systems by deciding on a limited set of key indicators that can be monitored to meet stakeholders’ priority information needs; creating a database that could be integrated with existing systems to track progress; building the human capacity to collect the required data and operate the M&E systems; and securing reliable sources of financing so that the crucial information can be collected and analyzed.

Eleven steps toward nationally integrated CSA MRV based on the lessons from four country assessments. Some countries have undertaken significant efforts on these steps, but much more work is needed. Source: CSA MRV profiles

Fulfilling all of these requirements will be a challenge. A fully functioning, coherent M&E system requires time and money. However, investment in improved M&E would bring significant benefits to national stakeholders, including building the evidence base on CSA; better prioritization of CSA investments; promotion of CSA awareness among stakeholders; improved information flows and coordination of CSA activities; and improved quality of information generated.

Read more:

- Report: Climate-smart agriculture measurement, reporting and verification in the Republic of Malawi

- Report: Climate-smart agriculture measurement, reporting and verification in the Republic of Zambia

- Report: Climate-smart agriculture measurement, reporting and verification in the Republic of Zimbabwe

- Report: Climate-smart agriculture measurement, reporting and verification in the United Republic of Tanzania

- Info note: Measurement, reporting and verification of climate-smart agriculture: Change of perspective, change of possibilities? (Download in French)

Andreea Cristina Nowak is an Environmental Policy Specialist at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF).