Our actions are our future: Achieving Zero Hunger by 2030

This World Food Day, we highlight how the work of CCAFS around nutrition helps in the fight to achieve zero hunger.

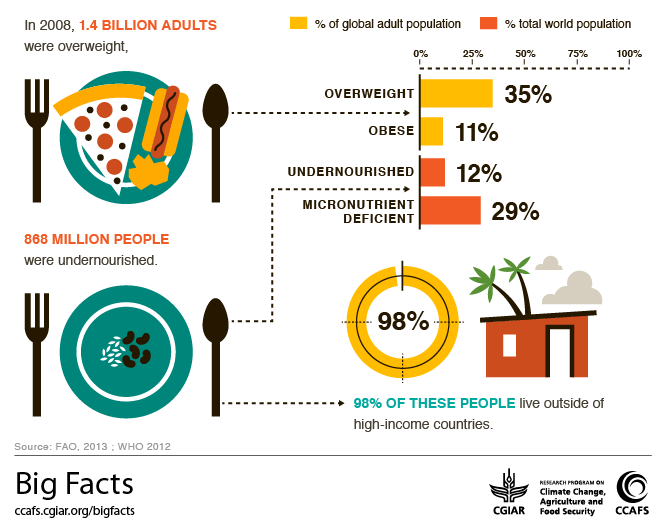

Despite the attention paid to agricultural development and food security over the past decades, there are still about 800 million undernourished and 1 billion malnourished people in the world. At the same time, more than 1.4 billion adults are overweight and one-third of all food produced is wasted.

Before 2050, the global population is expected to swell to more than 9.7 billion people. At the same time, global food consumption trends are changing drastically, for example, increasing affluence is driving demand for meat-rich diets. If the current trends in consumption patterns and food waste continue, it is estimated we will require almost 50% more food production by 2050.

CCAFS Big Facts on undernourishment and obesity. Source: CCAFS Big Facts

Climate-smart agriculture helps to improve food security for the poor and marginalized groups while also reducing food waste globally. It helps to address a number of important challenges, for example, malnutrition.

By 2022, CCAFS aims to have removed nutritional deficiencies of one or more essential micronutrients in 6 million more people, of whom 50% are women.

In this blog, we highlight some of our initiatives that address the issue of malnutrition that contribute to achieving Zero Hunger by 2030.

Making the case for dual nutrition and climate adaptation goals

|

People in households already struggling under the burdens of malnutrition don’t have the resources to become climate-resilient, while those suffering the negative consequences of climate change are at an increased risk of becoming malnourished in the face of degraded land, increased rainfall variability, and other climate change impacts. With so many already grappling with one or the other of these challenges, to truly have an impact, we must look for solutions that will address them both.

A report by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) with contributions from CCAFS and the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH) highlights the ways in which investments can be made for multiple benefits for livelihoods, agriculture, and nutrition. Case studies featured in the report show how working toward two different but related goals can help better achieve each. For example, an IFAD project in Bolivia is helping potato farmers use enhanced indigenous adaptation strategies to cope with reduced rainfall and depleted soils. The resulting improved harvests can help reduce malnutrition among vulnerable communities.

In order to develop solutions that address these combined challenges, CCAFS and AN4H recognize the need for collaboration on climate change and nutrition:

We might achieve good results working separately, but we could achieve great results by working more closely together."

Collaboration on gender is an excellent example of an area where our joint efforts can complement and benefit each other, enhancing progress towards achieving gender, nutrition, and climate change goals simultaneously.

Download the report: The Nutrition Advantage: Harnessing nutrition co-benefits of climate-resilient agriculture

Climate change impacts the concentration of key nutrients in crops

According to research by CCAFS and partners (see GCAN Policy Note, right), many food crops—including wheat, rice, barley, and soybeans—have lowered concentrations of nutrients when grown under elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations. This includes many nutrients that are important for overall health, such as iron, zinc, and protein.

On average, people around the world receive most of their nutrition from plants, including 63 percent of total dietary protein, 68 percent of zinc, and 81 percent of iron. Because so many people in the world get their nutrition from plants, and because plants are uniquely affected by higher CO2 concentrations, it is likely that large parts of the world would consume less protein, iron, and zinc coming from crops in 2050 unless significant measures are taken to counteract nutrient leaching.

This loss of dietary nutrients in foods could translate to increased nutritional deficiency for hundreds of millions of people already on the brink of deficiency—mainly those living in developing countries in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, based on dietary preferences for the crops most affected.

Countries have many ways to act to protect themselves now. For some crops, breeding programs could choose cultivars based on reduced CO2 sensitivity alongside other typically beneficial characteristics, such as high yields, heat tolerance, and drought and pest resistance. Many international organizations are actively working to create crop breeds with higher overall micronutrient contents, which would also work to offset these declines in nutrient density if adopted in regions that need them. CCAFS, through its learning platform on ex-ante evaluation and decision support for climate-smart options, is starting to work with several CGIAR centres on ex-ante analyses around climate- and nutrition-smart breeding.

Read our recent AgClim Letter: Hidden impacts: as carbon dioxide goes up, crop nutrients go down and sign up for future AgClim Letters here.

Biofortified crops in Burkina Faso

Combating malnutrition in a changing climate requires crops that are both climate-resistant and have high nutrient potential.

What is biofortification?

Biofortification is the process through which the nutritional quality of food crops is improved through agronomic practices, conventional plant breeding, or modern biotechnology.

One way that scientists are working to improve the lives of malnourished people in developing countries is through the development of crops that improve human nutrition.

The goal of biofortification is to grow nutritious plants which experts consider considerably less expensive than adding micronutrients to previously processed foods.

In 2017, through the BRAS-PAR project led by the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF), CCAFS introduced three biofortified varieties of millet and three different varieties of sweet potato in Burkina Faso. This improves the nutritional quality of the population (especially children, women and the elderly) and this, besides contributing to dietary diversification, also increases household incomes.

Left: Alimata Ouedraogo, one of the women who received cuttings of biofortified sweetpotato. | Group photo of the producers who benefited from the biofortified varieties and participated in the participatory evaluation of the tests. Right: Biofortified sweet potatoes. Photos: Dansira Dembele (CCAFS West Africa). Click to see more photos.

Policy is key

Achieving Zero Hunger will require not only technological changes on the part of many actors but also major behavioural shifts at various levels to help communities increase their adaptive capacity.

Policy is key to help strengthen the enabling environment for nutrition-related work. CCAFS is working with A4NH and a range of other policy partners to address some of the knowledge gaps and opportunities around national adaptation and investment planning to improve and diversify diets in target countries in several target countries in East Africa, South and Southeast Asia.”

Philip Thornton, CCAFS Flagship Leader on Priorities and Policies for CSA

This piece was edited by Lili Szilagyi, Communications Consultant at CCAFS.