Scenario planning and transformational change in Mali

Scenario planning has the potential to enable networking and learning across boundaries but it may not be sufficient to stimulate transformational change on its own.

Participatory scenario planning processes are believed to enhance participants’ systems understanding, learning, networking, and subsequent changes in practices. However, limited empirical evidence is available to prove these assumptions. The process may allow for an inclusive approach because of its complex systems analysis of food security challenges. It also involves multiple stakeholders bringing together their diverse knowledge and values to integrate climate adaptation into decision-making for future uncertainty and general innovation. Participatory scenario planning processes have the potential to generate social change necessary among participants to identify, adopt and implement innovation.

A journal article published in Futures titled ‘Can scenario planning catalyse transformational change? Evaluating a climate change policy case study in Mali’ explores the potential of scenario planning to generate transformational change.

What does a participatory scenario planning process look like?

A CCAFS project led by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in West Africa used participatory scenario planning processes to encourage improvements in climate policymaking.

The process was:

- Participatory. Stakeholders, including researchers, policy actors and practitioners with diverse knowledge, values and expertise came together to discuss and participate.

- Forward-looking. The participants discussed ways in which West Africa agriculture, food security and livelihoods could be affected by climate change and other global drivers, resulting in the creation of potential pathways.

- Locally applicable. The regional pathways were downscaled to be relevant at the district-level.

- Aimed at policy change. The goal was to improve district-level strategies, plans and policies to improve adaptation to climate change and other drivers of change.

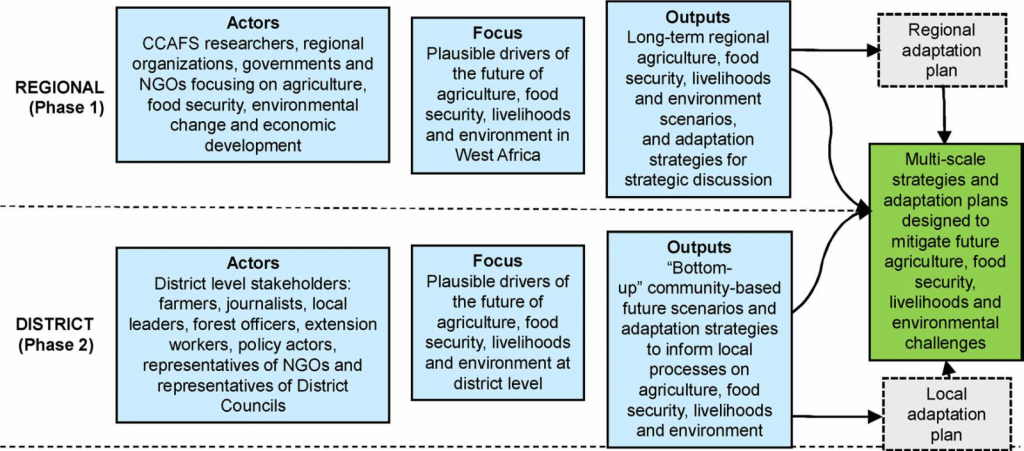

Researchers leading the process were studying how transformational change can take place. There were two phases of the scenario planning processes. The first phase of this process – regional exploratory scenario planning – had as a main goal the assessment of major and plausible future development pathways for food systems, environments and livelihoods in the West Africa region by engaging stakeholders in an explorative scenario process. The second phase – focus on downscaling of scenarios to a district-level – was used to generate information for local policy actors. This step was used to mainstream climate priorities into development plans and policies, and stimulate change of policy formulation processes.

See the figure below for a diagram of this process:

The regional (Phase 1) and sub-national (Phase 2) scenario planning processes, which supported the development of multi-scale adaptation plans. Source: Totin et al (2017).

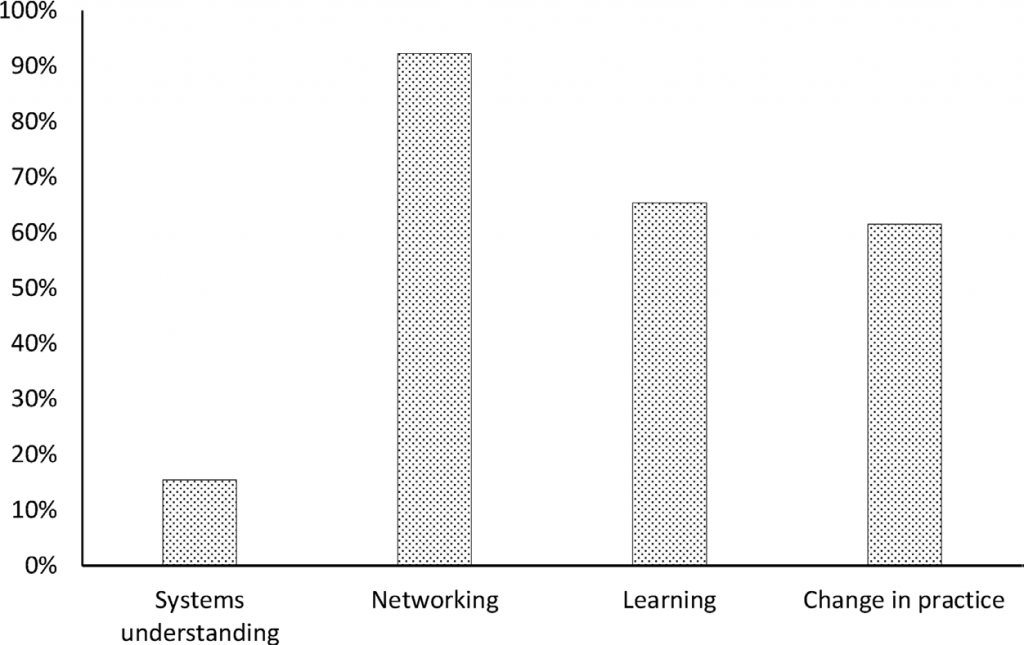

The ICRISAT researchers evaluated the outcomes of the process to find out whether there exist empirical evidences of social change that may have resulted from the scenario case study, against key attributes of (i) scenario systems understanding, which relates to enhanced comprehension of dynamism and complexity; (ii) relationship building, whereby scenario planning is an opportunity for interaction and social networks building; (iii) learning across boundaries, whereby participants gain new knowledge from stakeholders from different social levels or types; and (iv) changes in practices. The study mainly focused on a district level case study with more than 26 participants interviewed 12 months after the scenario planning workshop.

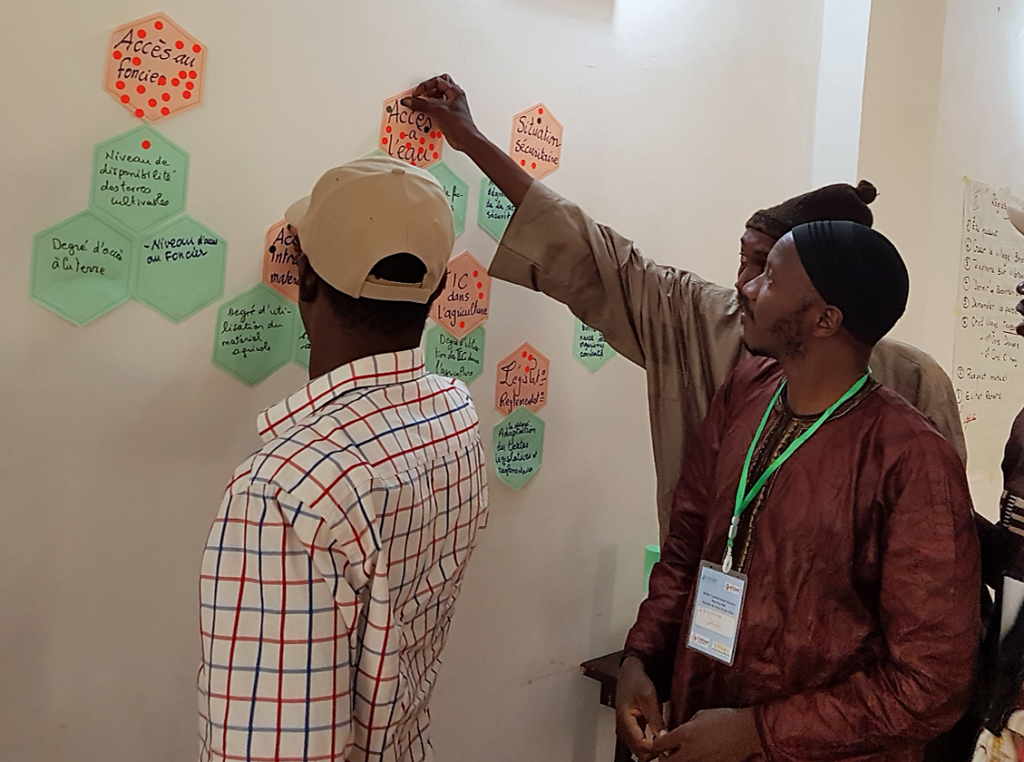

Participants work toward the creation of plausible future pathways during a multi-stakeholder scenario planning workshop. Photo: E. Totin

What were the outcomes?

Lead author of the study, Dr. Edmond Totin, remarked:

Participants see the scenario workshop as an interaction space, which helped to know more about the complexity of climate challenges and food security in the district. For some participants, the scenario workshops opened their eyes on new things. Being aware of this helps to think and plan forward.”

The participants shared how the scenario workshop influenced their lives and stimulated changes in practice as it allowed them to discuss things they did not know before, built networks and relationships with other partners, and also challenged them on other ideas. However, the workshop was least effective at stimulating systems understanding.

Proportions of scenario planning workshop participants (n = 26) that mentioned evidence of the four themes evaluated. Source: Totin et al (2017).

In conclusion, the scenario process alone may not be enough to stimulate transformation. Such scenario planning exercises should not be held in isolation but should instead be incorporated as one component of a broader and deliberate stakeholder engagement, learning and evaluation process.

What’s next?

The generation of extensive learning and social networks are critical elements of adaptive capacity, and hence the Phase 2 scenario planning workshop has at least contributed to the CCAFS theory of change in this regard, and created the foundation for future steps. Whether such institutional and policy change occurs will require long term and reflexive evaluation.

Download the article: Totin E, Butler JR, Sidibé A, Partey S, Thornton PK, Tabo R. Can scenario planning catalyse transformational change? Evaluating a climate change policy case study in Mali. Futures (online).

Interested in policies and priorities for climate-smart food systems? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive quarterly updates on our CCAFS work and occasional announcements.

Anne Miki is an Assistant to Project Manager for the Flagship on Priorities and Policies for CSA, Laura Cramer is Science Officer for the same Flagship, and Edmond Totin is the Project Leader for the ICRISAT project on which the research was based.