Agroecology: A key piece to climate adaptation & mitigation?

Agroecology can be defined as the combination of research, education, action & change that brings sustainability to the ecological, economic & social aspects of food systems is increasingly seen as an approach that can bring much-needed transformation to food systems.

A new academic review of over 10,000 studies finds substantial evidence that agroecological practices – like farm diversification, agroforestry and organic agriculture – can make a significant contribution in helping low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) meet their climate adaptation and mitigation targets through their food systems.

The study found that agroecology can play a major role in climate change adaptation and mitigation. However, we still don’t have enough data and evidence on what works, where and why. So, what does the available evidence tell us?

What the evidence tells us

Climate change adaptation

- Farm diversification had the strongest body of evidence for impacts on climate change adaptation, which included positive impacts of diversification on crop yield, pollination, pest control, nutrient cycling, water regulation and soil fertility.

- Substantial evidence exists for climate change adaptation associated with practices and systems aligned with principles of agroecology. However, more analysis is needed to understand agroecology’s resilience to extreme weather conditions.

- Some agroecological practices, like agroforestry, have positive impacts on biodiversity, water regulation, soil carbon, nitrogen and fertility and buffering temperature extremes. Others, like organic agriculture, improve regulating (pest, water, nutrient) and supporting services.

Climate change mitigation

The evidence on agroecology’s impact on mitigation is modest, except for enhancing carbon sequestration in soil and biomass.

Where there is strong evidence:

- Tropical agroforestry had the strongest body of evidence for impacts on mitigation, which had associated sequestration of carbon in biomass and soil.

Where there is weak evidence:

- As the GHG footprint of outcomes depends on where system boundaries are drawn, more multi-scalar analyses are needed to capture flows of inputs and impacts beyond the farm scale, especially in LMICs where there is almost a complete lack of data on GHG emissions from tropical agriculture.

Where there is moderate evidence:

- There is a moderate and growing body of evidence for organic agriculture increasing soil carbon sequestration.

- Evidence of nitrous oxide mitigation was modest for tropical agriculture overall, and data on methane generation or mitigation was also limited.

- Evidence from the global North suggests that reliance on organic nutrient sources and organic farming will likely avoid increased nitrous oxide emissions compared to use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer.

Adaptive capacity

- Evidence suggests that agroecology provides more climate change adaptation and mitigation than conventional agriculture by emphasizing locally relevant solutions, participatory processes and co-creation of knowledge.

- Specifically, co-creation and sharing of knowledge supported farmers’ capacity to adapt to local conditions.

- Multiple lines of evidence show that engaging with local knowledge through participatory and educational approaches are effective at adapting technologies to local contexts, thereby delivering improved adaptation and mitigation.

Yields

- Evidence for trade-offs exists between yields and climate change adaptation and mitigation, but it was not systematically reported.

- There are win-win outcomes for yields and climate change mitigation associated with crop diversity and organic nutrient management, but not necessarily for organic farming or agroforestry.

Data gaps

- There is a clear need for high-quality, long-term, research on farms and at landscape scales that compare agroecology against alternatives like conventional or climate-smart agriculture.

- A large data gap was found for agricultural GHG emissions and mitigation, with almost no evidence from the global South. There were also evidence gaps for agroecology approaches involving livestock integration, landscape-scale redesign and for multi-scalar analysis.

- A major concern is to what extent scaling up agroecology may restrict farmers’ options and becomes a poverty trap by maintaining the status quo by not providing access to possible growth through industrial and corporate models.

- There is a lack of data or scenarios showing the impacts of agroecological transitions on economic development.

Donor investments

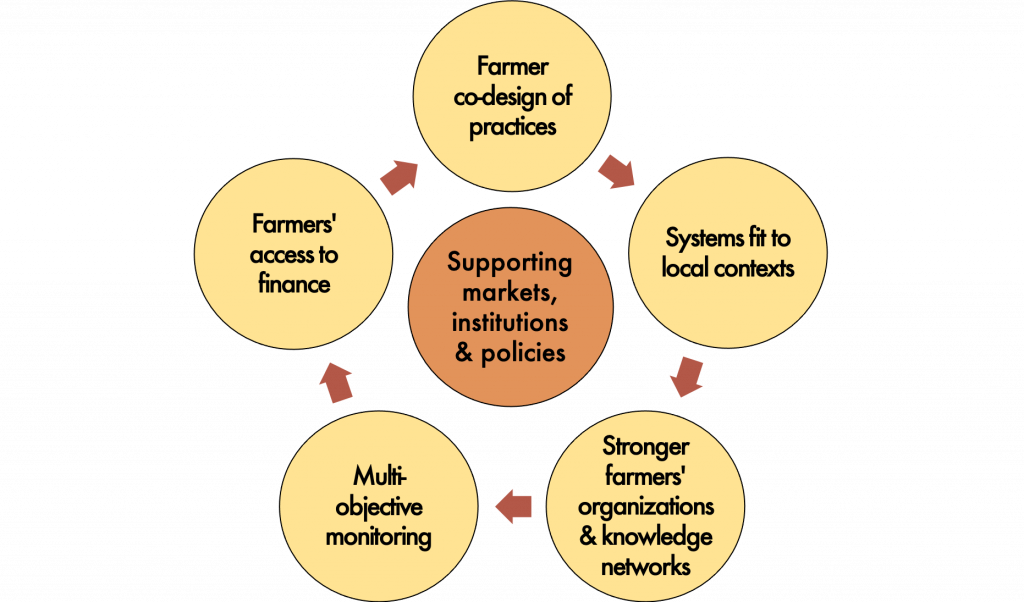

Improve investment in agroecology for climate change will require long-term funding modalities, outcome target setting that includes environmental services and climate benefits, and systemic change and incentives to build farmer capacities (Fig 1). Rather than treating climate change adaptation and mitigation as co-benefits, global food systems must be actively managed for climate change benefits.

Figure 1. Key elements of exiting agricultural development programs to increase support for agroecology and climate change outcomes.

What actions are needed?

Tackling climate change has always required broad cooperation and diverse approaches. Implementing agroecology across organizations with different political visions for development will require transcending the many labels for sustainable agriculture and climate change (e.g., climate-smart agriculture, regenerative agriculture), including agroecology. The point is to spend less time debating what agroecology is, and more time on how it can be used to improve agricultural mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

Recommendations from the review

- An outcome-based approach is needed to understand the performance of integrating agroecological principles and climate change adaptation and mitigation indicators.

- Direct agricultural development investments to agricultural diversification, local adaptation, and pathways to scaling both.

- Increase investment for research on agroecology’s resilience to extreme weather events and climate change mitigation outcomes.

- Invest in research to analyze approaches aligned with agroecology relative to other agriculture development approaches, across all scales and regions, for outcomes in multiple dimensions and their trade-offs, including cost-effectiveness.

Sieglinde SNAPP, Michigan State University, USA

Yodit KEBEDE, French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD) and The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

Lini WOLLENBERG, CCAFS and University of Vermont (Corresponding author - lini.wollenberg@uvm.edu)

Kyle M. DITTMER, CCAFS and The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT

Sarah BRICKMAN, University of Vermont

Cecelia EGLER, University of Vermont

Sadie SHELTON, CCAFS and University of Vermont