Bridging climate forecasts with farmer realities: The story of Seck and Ousmane

Kaffrine, Senegal’s main agricultural region, is the setting for a new project from the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Together with the National Meteorological Agency (ANACIM, by its French acronym) and the extension department of the Senegalese Ministry of Agriculture, CCAFS is working to improve the decision making processes of small-scale farmers by facilitating their access to agroclimatic information and increasing their capacity for understanding and uptake of this information.

The alliance is embodied by two key Senegalese experts who serve as guides and beacons for the goal of successful inter-institutional collaboration: Ousmane Ndiaye and El Hadji Moussa Seck.

Ousmane Ndiaye, the project’s coordinator, is a meteorologist and produces seasonal forecasts at ANACIM – the numbers man. Hadji Moussa Seck, on the other hand, brings the practical aspect to the table: he is in charge Senegal’s governmental agricultural extension program in Senegal, and he knows how to make information that is useful to a scientist into information that is also useful to a farmer.

The scientist Ousmane has a lot to learn from Seck, it turns out, and vice versa.

Ever since I’ve been working with Seck,” says Ousmane, “I’ve been learning more and more about how farmers work and act. I’ve learned how to get close to them, how I should speak and work with them."

Seck was already well known and respected in the Kaffrine area, he explains, a fact which greatly facilitates the integration of project partners into the community.

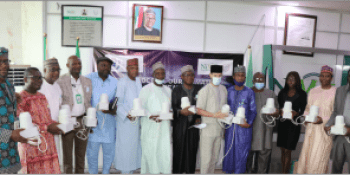

Farmers in Kaffrine have benefited from a collaboration that makes seasonal climate forecasts relevant and understandable from a local context. Photo: A. Jarvis (CIAT).

As extension coordinator for Kaffrine, it is Seck that distributes fertilizers and subsidized seeds to farmers in the community and manages most of the agricultural problems in the region. He knows more about the trials and tribulations of farming in the area than just about anyone.

My work,” says Seck, “has changed a lot since I’ve started collaborating with Ousmane. It was like the rebirth of all my labors; before this nobody took much note of my services. Now that we have this access to climatic information, people are actually seeking us out. They think of us when they have a problem. That has never happened before!” he boasts.

CCAFS researchers hosted a combined interview with these two individuals who embody a successful and fruitful partnership.

What has the institutional collaboration between ANACIM and government extension services achieved so far?

“What we’ve been able to do is employ an integrated and multi-disciplinary focus on the themes of climate, agriculture and food security,” they say. “From the point of view of the farmers, we have been able to break down their climate information needs, their way of making decisions, and their manner of understanding the climate in a participatory way.”

Seck and Ousmane continue,

With this collaboration, farmers are getting day-by-day climate information that lets them make accurate decisions. They can plan better for the start of the rains, understand how precipitation might behave during the harvest cycle – they can even get timely information on the current season.”

What stands out, they say, is that learning has clearly taken place among the farmers. The partnership has been able to achieve notable changes in the decision making process of the small farmers in the region.

What have been the key work principles that you have used to reach your objectives up to now?

Ousmane tells us,

Taking advantage of existing agricultural networks at the local level has been crucial for our success. These networks bring confidence and legitimacy with them, like for example with the governmental extension services and farmer associations that have been in existence for many years. Or how ANACIM has enabled equity in terms of access to climatic information, from themselves down to local extensionists and farmers.” Osmane continues, “It was natural to work with Seck from the beginning.”

Seck explains how the alliance works from the operational perspective:

Ousmane sends me climate information, and I’m in charge of disseminating it on a large scale. My working network includes local radio, leaders of rural communities, some religious representatives, representatives from farmer associations, and the farmers themselves.”

This prodigious networking capacity has lent Seck the nickname “Mr. Meteo” in his department; He receives endless calls from farmers needing climate information before they go out to work their land.

Collaboration enriches the work and allows the efficient achievement of the project’s objectives, according to these two linchpins of rural climate information services. In Ousmane’s opinion, it bears mentioning that one person alone could not generate the impact that they are looking for in terms of ensuring that climate information reaches farmers.

That’s especially true,” he says, “seeing as there is no way for us to know what climate information is going to be relevant, nor how we might best translate it so that it is understandable and useful for the farmers.” They need a partner like Seck to make that happen.

“Seck and I are complementary,” concludes Ousmane.

I have the climatic foresight, he has the reality on the ground. Our work is to join those two aspects to make climatic variability less of a mystery for the farmer.”

As they continue to build bridges between scientists and farmers, Seck and Ousmane represent a successful partnership from which we have much to learn.

This post was originally published in Spanish on the DAPA blog.

To read more, see Andy Jarvis's blog "Generating a climate conscience through south-south learning" and a photostory of the exchange "When Colombia met Senegal."

Fanny Howland is a visiting researcher at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) in Cali, Colombia, working on Capacity Strengthening and Knowledge Management.