Big Facts: Policy and Finance

This final blog post of the Big Facts series focuses on policy and finance aspects of climate change, agriculture and food security.

Previous posts have focused on circumstances, impacts, and solutions, both globally and in different regions of the world. What these posts have in common is that without the right policies to structure this work and money to finance it, the challenges loom larger and solutions are harder to put in place.

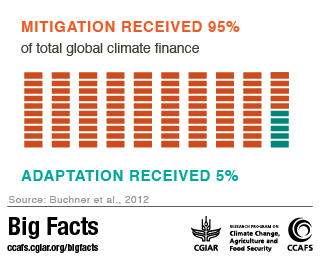

Smallholder farmers, food security and adaption must come first; however, currently mitigation receives the lion’s share of finance.

Policy-makers need to find ways to increase public and private finance to adaptation measures.

Climate Finance

Modes of finance to the climate change and agricultural area can be divided into two categories: climate finance and mainstream agricultural finance.

Mainstream agricultural finance mechanisms include:

Official Development Assistance (ODA);

Foreign Direct Investment;

Private domestic sources, such as banks, microfinance, and companies in the (agricultural) supply chain; and,

Funding from charitable foundations, NGOs, and farmer organisations.

Climate finance mechanisms include:

The Green Climate Fund, which provides support to developing countries to limit or reduce their greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation) and to adapt to the impacts of climate change (adaptation);

Regulated carbon markets such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) under the Kyoto Protocol and the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme;

National Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) and the Adaptation fund of UNFCCC;

The Climate Investment Funds, administered by multilateral development banks;

Voluntary carbon markets; and

Company supply chain standards on climate and eco-certifications, and funding from charitable foundations, NGOs and farmer organisations.

Policy approach

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has created several vehicles to help structure national agricultural and climate policy.

In 2010, at the 16th Conference of Parties (COP16) to the UNFCCC, the Parties established the National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) plans to enable Least Developed Countries (LDCs), a group of low-income countries, to “formulate and implement national adaptation plans”. These plans will aid them in planning and implementing priority activities around their immediate needs to adapt to climate change. Many of these countries lack the financial capital and the political systems to deal with these challenges alone. Many NAPAs include agriculture, food security, water resources and disaster management as priorities.

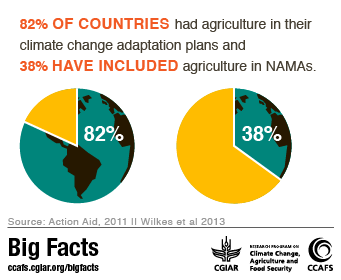

National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) aim at identifying medium-term and long-term adaptation strategies. They aim to “reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, by building adaptive capacity and resilience,” and to “facilitate integration of climate change adaptation into relevant new and existing policies, programmes and activities”. The NAP process is seen as a larger process for enabling the planning and implementation of adaptation at the country level, and builds on the experience of the LDCs in addressing adaptation needs through the NAPA process (Kissinger and Namgyel, 2013). While these have been prepared and implemented only by the LDCs, other low- and middle income Parties were invited to use these when formulating their own plans. These plans are currently under development in many countries around the world, and will produce an array of outputs ranging from concrete action plans to build climate resilience, to assessments of capacity gaps, to strategies for mainstreaming climate policies. The NAP process may result in long-term national plans, regional or local adaptation policies, or sector-based development strategies, depending on the specific situation in each country.

Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) are sets of policies and actions that countries undertake towards their international commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There are 55 formal NAMA proposals, 21 of which propose actions in the agriculture sector. A number of NAMAs are also under development but have not been officially submitted to the UNFCCC, bringing the total number of NAMAs to 62 in 30 countries. Several NAMAs also relate to national deforestation reduction strategies (i.e. Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+)), but these tend to elaborate very little on agricultural abatement measures (Wilkes et al. 2013).

Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMAs) are sets of policies and actions that countries undertake towards their international commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There are 55 formal NAMA proposals, 21 of which propose actions in the agriculture sector. A number of NAMAs are also under development but have not been officially submitted to the UNFCCC, bringing the total number of NAMAs to 62 in 30 countries. Several NAMAs also relate to national deforestation reduction strategies (i.e. Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+)), but these tend to elaborate very little on agricultural abatement measures (Wilkes et al. 2013).

Countries have also introduced a range of policy vehicles to coordinate and mainstream climate policy and to include the UNFCCC elements. Government mechanisms include climate action plans, low emissions development plans and climate change adaptation plans.  To increase effectiveness of these measures, policy integration and coordination is needed. Climate-smart policies aim to combine policies on food security, adaptation, and mitigation to achieve sustainable agricultural development. There has been a rapid uptake of these policies by the international organisations and governmental institutions recently, but climate-smart interventions are highly location-specific and knowledge-intensive, making the policies challenging to implement, partly due to a lack of appropriate tools and the necessary experience (FAO, 2013).

To increase effectiveness of these measures, policy integration and coordination is needed. Climate-smart policies aim to combine policies on food security, adaptation, and mitigation to achieve sustainable agricultural development. There has been a rapid uptake of these policies by the international organisations and governmental institutions recently, but climate-smart interventions are highly location-specific and knowledge-intensive, making the policies challenging to implement, partly due to a lack of appropriate tools and the necessary experience (FAO, 2013).

Sources:

FAO (2013) – the FAO CSA Sourcebook: http://www.fao.org/climatechange/climatesmart/en/

Wilkes et al (2013) National integrated mitigation planning in agriculture: A review paper. http://www.fao.org/docrep/017/i3237e/i3237e.pdf

Kissinger and Namgyel, 2013 http://ldcclimate.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/ldcp13_napas-and-naps.pdf

Now you can get all the Big Facts on the links between climate change, agriculture and food security at ccafs.cgiar.org/bigfacts2014. The new site features over 100 stunning infographics that illustrate the most up-to-date, thoroughly researched information on these topics.

Big Facts is also an open-access resource. You can download and share the graphics with your friends and colleagues and use them in your presentations and reports. Please do not hesitate to send us any suggestions for improvements, either by commenting below or sending us an email.

This story is part of a series focusing on the Big Facts on various topics and in different regions; join the conversation at ccafs.cgiar.org/blog and on twitter using #bigfacts