Assessing climate change vulnerability and its effects on food security: Testing new tools in Tanzania

Understanding local vulnerability to climate change is critical to better mitigate climate risks and promote adaptation strategies for rural communities.

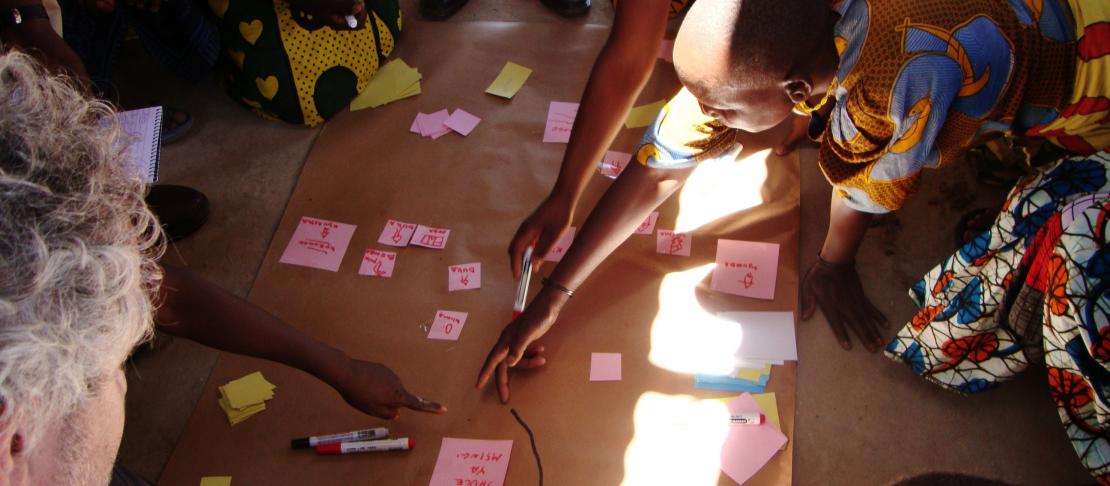

Extreme climate events and variability are already affecting the food security of many, particularly those living in stressed environments. In the light of this, a team of researchers conducted a participatory workshop in Hombolo, Tanzania in late October, to test tools designed to analyze climate change vulnerability in relation to food security.

Now it is time to share the methodology used and some of the first impressions from the field activities!

The toolkit provided below is a step-by-step manual for researchers and local actors to work together, to identify the main climate impacts affecting a community’s livelihoods and food security. It was developed by the Institute of Development Studies and Bioversity International based on a tool used by GIZ in Mexico.

Using the toolkit can help design ways that a community can manage and adapt to climate risks, while taking into consideration other relevant constraints such as social, economic, political, gender-specific or ethnic factors.

A multidimensional understanding of social vulnerability

Below are five identified dimensions that make individuals and communities more vulnerable to climate change.

1: Livelihood strategies - What are the local livelihood strategies, how climate-sensitive are they and how important are they for food security?

2: Local wellbeing - What are the local indicators of wellbeing and do the current livelihood strategies manage to provide it?

3: Individual adaptive capacity - What is the capacity at an individual or household level to adapt to climate change?

4: Collective adaptive capacity - What is the capacity at a local level to take collective measures to adapt to climate change?

5: Governance and power relations - How effective and capable is the governance system to provide support to adapt to climate change and provide food security?

A range of traditional participatory tools can be used to cover research questions related to climate vulnerability and food insecurity including village mapping, seasonal calendars, climate risk ranking and Venn diagrams. Semi-structured interviews with key informants and vulnerable households can also be useful.

The participatory workshop was convened by researchers from Bioversity International, African Biodiversity Conservation and Innovations Centre (Kenya), National Genebank of Kenya, Tanzania Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute and the Institute of Development Studies,

Testing the toolkit in Tanzania

Researchers Carlo Fadda and Martina Ulrichs headed to Sokoine, Zepisa, a small village of Hombolo district in Tanzania to assess the toolkit in action. This is their report back:

Although the assessment ideally requires five days, in this case we already had information from previous household surveys, so we felt that we could fill in information gaps in less time.

So in just two and a half days, we did a transect walk, village map, seasonal calendar, well-being ranking, seed systems analysis, crop preference anking, Venn diagram, climate risk ranking and coping mechanisms matrix.

Most of the tools were used separately for men and women to capture gender-specific perceptions.

We worked with about 20 men and women from different age groups, mostly farmers, livestock herders, crop traders, shop keepers, and those making and selling local brew. However, we soon found out that these categories did not capture their highly diverse activities, livelihood strategies and coping mechanisms.

The community is mainly affected by increasing drought, erratic rain and pests, with the addition of stronger winds and an increase in human diseases. The level of detail we obtained about how these impacts affect livelihood strategies and in particular different varieties of local food crops, was surprising.

We learned what their preferred crop characteristics were, and why farmers consider it worthwhile to plant certain crops or not. Farmers sow a large number of crops - sometimes more than fifteen! - including staples such as maize, sorghum, and finger millet, cash crops simsim, sunflower and ground nuts and food crops for example cowpea, vegetables, wild fruits and vegetables which are very important for enriching diets during specific times of the year.

Their seasonal calendar provided us with a more holistic picture of agricultural production, their periods of food security and food shortage (worst in February-March). In times of food shortage, farmers often start harvesting crops prematurely, which is called 'green harvesting'.

They also find ways to bridge food gaps – generating income by selling firewood, burning and selling charcoal, seeking casual employment outside the village and collecting wild fruits and vegetables. These activities are vital since they help generate food and income in times of shortage, but they are also considered a last resource since they are the most labour-intensive.

Clear patterns of vulnerability also emerged, for example, poorer households will sell their crops to traders at a low price to meet immediate cash needs, only to buy food back in times of shortage when the price is high.

Vulnerability patterns, such as selling off crops immediately after harvest to get cash, was found in a recent assessment in Tanzania. Photo: ENVIU

The toolkit allowed us to understand market systems, patterns of food access and availability, as well as the informal mechanisms of exchanging and buying seeds. These can be an important entry points for introducing improved crop varieties that fit the local context, and increase the probability of take-up by the farmers.

There are of course limitations, but with prior local research, even a two and a half day vulnerability assessment can provide a wealth of information. However, we need to figure out how such an assessment can be incorporated into a wider research undertaking or project cycle, so that it doesn’t remain an isolated piece of information.

We just got back from the field and are still shaking off the dust from our trousers, but we will soon produce a paper on the main findings and methodology from the Sokoine vulnerability assessment. We will also be sharing the toolkit, so watch this space!

Caption for first photo: Village mapping

The climate vulnerability assessment toolkit is an output of two CCAFS projects led by Bioversity International: ‘Climate Change and Food Security Vulnerability Assessment’ and ‘Varietal diversification to manage climate risk in East Africa’.

Carlo Fadda is theme leader of Productive Agricultural Systems at Bioversity International. Martina Ulrichs is a research consultant at the Institute of Development Studies.