First satellite-based insurance trial in Bangladesh helps farmers recover from flooding

An innovative Index Based Flood Insurance to assist the insurers with claim settlement.

When Ms. Eva Begum’s house was damaged by floods during the 2019 monsoon, she didn’t have to worry. As a participant in a trial of a satellite-based flood insurance scheme, she was entitled to compensation for loss of earnings as an agricultural laborer. She was able to use the BDT 3600 (USD $43) payout she received to quickly repair her home and get back on her feet. Without the insurance, she said, she would have had to take out a loan with interest, and would have been anxious about making the repayments.

Ms. Begum was one of 3,500 smallholders (750 households) from two upazila (sub-districts) of Gaibandha district, Bangladesh, to benefit from the scheme. In total, the farmers received compensation of BDT 2.67 million (USD $31,500). The initiative, developed as part of Oxfam Bangladesh’s Resilience through Economic Empowerment, Climate Adaptation, Leadership and Learning (REE-CALL) program, was the first in the country to use satellite data to insure low-income rural households against climate-related risks.

Under the REE-CALL program, smallholders took out capital loans from microfinance companies. Oxfam Bangladesh wanted to provide insurance so that farmers would be financially secure even if flooding damaged their crops. Therefore, it joined forces with the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), the CGIAR Research Programs on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE), insurance firms Green Delta Insurance Company (GDIC) and Swiss Re, and microfinance company SKS Foundation, to develop an innovative Index Based Flood Insurance (IBFI).

To develop the underlying model, IWMI researchers used 250m by 250m data from National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA’s MODIS) satellite to map inundation on a daily basis from 2001 to 2018. This helped to highlight historic flooding patterns and show where inundation was most likely to occur in the future. They validated the model using water-level data from the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) and European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel-1 SAR satellite data. Insurance experts then designed payout conditions around anticipated timings and levels of flooding, potential crop damage, wages and other socioeconomic factors. They set the sum insured at BDT 12,000 (USD $140).

The model works by calculating, from the satellite images, the proportion of land that is inundated in relation to the total geographical area of the upazila in question. If flooding occurs on seven consecutive days, with at least 40% of land inundated, farmers receive 20% of the sum insured; if flooding occurs for this period across at least 50% of the area they are paid 40%. For prolonged flooding across 14 consecutive days that affects at least 40% of the area, they receive 30% of the sum insured. And they are entitled to 50% of the sum if the inundation affects at least 50% of the area for this period.

Putting the model to use

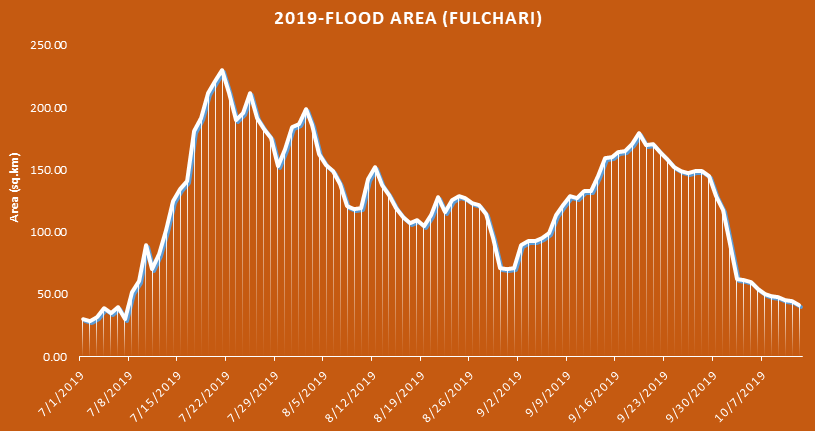

The heavy monsoon rains in July 2019 affected 7.3 million people in Bangladesh. Nine districts were severely flooded, including Gaibandha. IWMI and partners calculated that households in the two participating sub-districts of Fulchari and Sughatta should be compensated by BDT 2,617,200 (USD $30,850) and BDT 55,200 (USD $650) respectively, for damage to crops incurred during the insurance period of August to October.

The area of Fulchari sub-district affected by flooding on particular dates during the 2019 monsoon. Source: IWMI

The payout took just two weeks to ascertain. Shortly after, farmers received individual payouts direct to their bank accounts. “IWMI’s support in providing remote sensing data and analysis greatly assisted the insurers to develop the claim settlement part of the IBFI, and to calculate payouts for distribution among 750 destitute households in Gaibandha,” says Mr. K. N. M. N. Azam, Senior Program Officer, Oxfam, Bangladesh, who led the project.

In January 2020, an event was organized by Oxfam and held in the Jahur Hossain Chowdhury Hall, National Press Club, in Dhaka, to publicize the insurance payout. At the meeting, there were calls for larger numbers of farmers to be supported by such insurance schemes. Fazle Rabbi Miah, the incumbent Member of Parliament for Gaibandha-5 and current Deputy Speaker of the Bangladeshi Parliament, suggested that the Director General of the Department of Disaster Management should allocate money for paying premiums as part of disaster preparedness, to reduce the suffering of vulnerable people when disasters occur.

In the past, poorer farmers were excluded from insurance as they could not afford the premiums. However, IBFI’s use of satellite technology negates the need for wide-ranging checks on the ground, keeping premium rates within affordable limits and ensuring claims can be settled quickly. “IWMI’s support in preparing standard flood index insurance data products has helped GDIC to explore new opportunities in agricultural insurance,” says Ali Tareque Parvez, Senior Vice President, Agriculture Team, Green Delta Insurance, Dhaka.

Disasters on the rise

Across South Asia, climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of weather-related disasters, displacing populations, exacerbating conflicts and hindering efforts to reduce poverty and inequality. Such events particularly affect poor and vulnerable people who depend on agriculture for livelihoods and subsistence. At the present time, the risks are even greater than usual because South Asian nations face the prospect of the current coronavirus pandemic coinciding with extreme weather. With the monsoon season advancing as lockdown measures are being put in place, it is possible that flooding could displace thousands of people already made vulnerable by pandemic-disrupted supply chains.

IWMI is now working with Oxfam Bangladesh, UN World Food Programme (WFP) and partners to expand the IBFI to another district in the northern part of the country. Scaling up such insurance schemes has the potential to benefit not only farmers but also governments and the private sector. Building farmers’ resilience to both climate shocks – and other risks – in developing countries, will mean governments have a greater chance of reducing the costs of post-disaster recovery.

Read more:

- News update: Mainstreaming technology provides key solutions for disaster risk mitigation

- Policy Brief: Insurance as an agricultural disaster risk management tool: evidence and lessons learned from South Asia

- Blog: Time to double down on the triple win of disaster risk reduction

Giriraj Amarnath is Research Group Leader of Water Risks and Disasters (WRD) at IWMI.