Identifying climate service entry points to improve nutrition and climate adaptability in Vietnam

Vietnam has been deemed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to the impacts of climate change.1 Increasingly frequent extreme weather events, saltwater intrusion into the country's river deltas, and more climate variability threaten the country's progress towards attaining the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Progress on food production and nutrition face particularly high risks.2 Vietnam’s continued progress on reducing malnutrition, improving public health, and developing its economy will be tied to its ability to create a resilient food system as it contends with future climate uncertainty.

One strategy to reduce the risk of climate variability on agricultural production and nutrition is the use of climate services. The International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) has championed the application of climate services to increase the adaptive capacity of food system actors to cope with shocks and achieve SDG 2.3 As a result, IRI has become a key partner of CCAFS, while hosting the Flagship on Climate Services and Safety Nets within its institution at Columbia University.

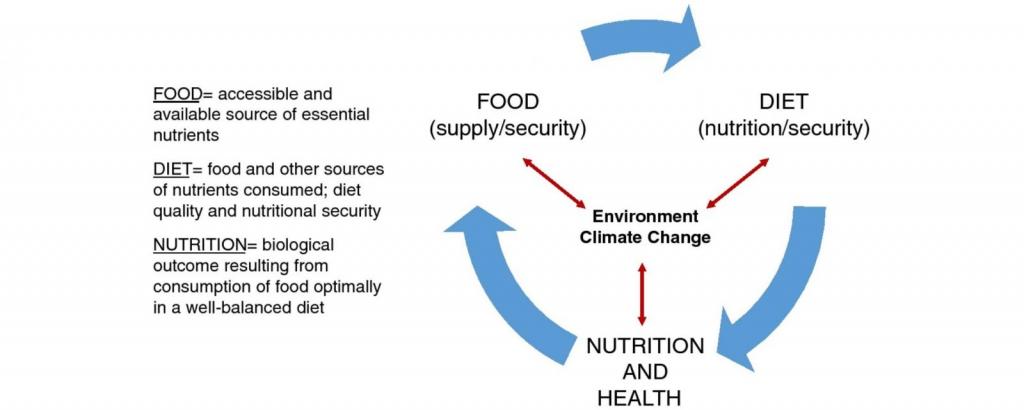

A figure demonstrating the intersection between nutrition, food, diet, and environmental change. Source: Raiten & Aimone, 2017.

Efficient collaboration across the fields of agriculture, nutrition, and health requires a strong understanding of the interdependence of these sectors.4 For Vietnam, this collaboration will become increasingly necessary to improve nutrition, food security, and public health as climate-related hazards worsen.

In order to better discern this complex web of stakeholders in Vietnam, IRI, through the “Adapting Agriculture to Climate Today, for Tomorrow” (ACToday) Columbia World Project, conducted a landscape analysis of Vietnam’s nutrition sector to discover potential entry points for climate services. This analysis was done in collaboration with the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH). This research will contribute to the progress of ACToday as the program works alongside the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)’s DeRISK Southeast Asia initiative to build the institutional capacity of the government to generate, tailor, and communicate climate services to improve climate risk management in Vietnam.

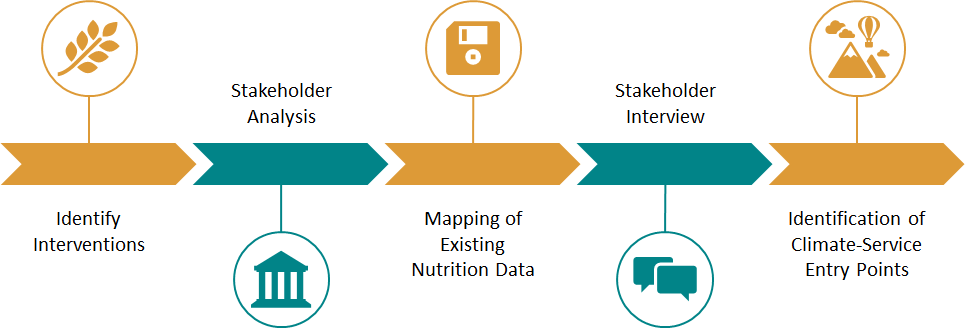

The analysis and research process followed the structure outlined below:

Research methodology undertaken for nutrition landscape mapping. Source: Pranav Singh (ACToday).

Key Findings

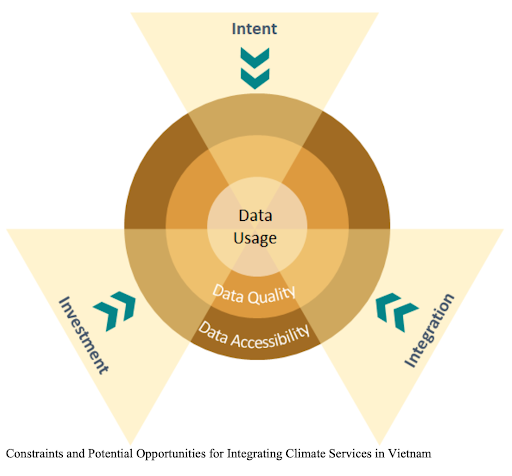

The analysis focused largely on the systemic issues affecting Vietnam, which can be broadly classified into informational and institutional constraints. Due to the correlation between these constraints, efforts to improve upon the status quo need to be comprehensive in strategy, and simultaneous in execution.

Informational Constraints: Inclusion of climate information into nutrition programs and policy suffers from a series of data-related constraints hampering accessibility of data, affecting the quality of data, and the analytical capacity available within institutions. Ultimately, this limits the utility and effectiveness of the country’s climate services.

Institutional Constraints: While correlated, institutional constraints may have an even greater role—arguably serving as the underlying cause of the other systemic issues. In our analysis, we found:

- Insufficient evidence of the utility of climate services making high-level policy makers reluctant to enact institutional changes

- Inadequate infrastructure for both collection and dissemination of information, and

- A need for improved coordination within and across government and development partners alike

On the other hand, the above institutional constraints have the potential to serve as levers of change, offering clear priority areas to concentrate our efforts.

Shows constraints and potential opportunities for integrating climate services in Vietnam. Source: Pranav Singh (ACToday).

From our interactions with experts across the nutrition landscape, we identified some of the critical gaps, associated with the above constraints:

- Current data sharing mechanisms between data collecting agencies and downstream users are cumbersome. Data is shared through reports, rather than as raw data, which limits users’ ability to analyze the data.

- Access to information, particularly in poor and mountainous provinces, is severely limited. This prevents precise predictions and differentiated responses across Vietnam’s numerous geo-climatic zones.

- The analytical capability to use climate services for dietary assessment, by measuring food production and availability, needs to be improved. This is particularly acute at the local level where resources, capacities and expertise is limited.

The most important (challenge) is the little amount of research conducted and evidence created in the country to highlight the linkages between various food system sectors and climate change with regards to policy making. The capacity of local governments to understand the linkages between various sectors and with climate is still limited."

Tuyen Huynh, Country Head of Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH), Vietnam

Potential entry points

In order to improve and integrate usage of climate information into nutrition interventions, a common framework—both in terms of inter-agency coordination as well as data interoperability—is needed among nutrition landscape stakeholders. In addition, with the upcoming National Nutrition Strategy (2021-30), there is an unprecedented opportunity to integrate climate information into program design and evaluation. This would require capacity building within key government institutions (such as the General Statistics Office, the National Institute for Nutrition, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development), and increased investment into upgrading the current infrastructure.

Gender With a majority of nutrition policies and interventions focusing on improving the nutrition of girls, government agencies have acknowledged the disproportionate vulnerability of women to malnutrition and climate-related risks. Yet, these agencies simultaneously admitted the need to formally mainstream gender throughout their programs. This has spurred key ministries to implement a range of economic empowerment programs for women and diversity requirements. These actions are a good step forward and should be complemented by addressing unequal access to information, productive assets, and household resources. |

Development partners in Vietnam, such as CIAT, USAID, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), CCAFS, and IRI, can play an important role in building this capacity. Not only can they offer ready-made platforms to launch initiatives, but they can work within and across key institutions to build technical knowledge and foster partnerships that encourage long-term coordination to improve climate service integration into nutrition interventions. IRI/ACToday exemplifies this approach through their work training officials and hosting collaborative workshops with prominent ministries and NGOs, facilitating the development of relationships and technical knowledge that will be central to the adaptation of Vietnam’s food system. Development partners can also open up government funding by demonstrating the empirically-based benefits of integrating climate services into nutrition interventions.

Integrating climate services into nutrition policy to combat food insecurity and malnutrition in Vietnam will require a great deal of coordination. With some support, Vietnam and the highly skilled professionals working across nutrition, agriculture, and climate services can address this challenge.

Read more

- Working paper: Nutrition landscape and climate in Vietnam: Identifying climate service entry points

- Research project: Adapting Agriculture to Climate Today, for Tomorrow (ACToday) in Vietnam

- Video: Gender & climate services in Vietnam

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5°C: Summary for Policymakers. IPCC Special Reports. Retrieved from: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/. Tatarski, M. (2018). New Climate Change Report Highlights Grave Dangers for Vietnam. Mongabay: News and Inspiration from Nature's Frontline. Retrieved from: https://news.mongabay.com/2018/10/new-climate-change-report-highlights-….

- USAID. (2020). Climate Change. USAID: Vietnam. Retrieved from: https://www.usaid.gov/vietnam/climate-change.

- Turner J. 2019. More than rice: The future of food security in Vietnam. The International Research Institute for Climate and Society. https://iri.columbia.edu/news/more-than-rice-the-future-of-food-securit…

- Raiten D.J. & Aimone A.M. 2017. The intersection of climate/environment, food, nutrition, and health: Crisis and opportunity. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 44, 52-62.

Pranav Singh has recently completed his Master of Public Administration program from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, where he focused on understanding the challenges at the intersection of nutrition, agriculture and climate change.