How good are climate models at predicting impacts on crops?

New Reports Offer Insight into Reliability of Future Climate Projections for Agriculture.

What effect will rising temperatures and changes in precipitation have on the ability of farmers to grow crops and feed the earth’s growing human population in the coming decades? Three new regionally focused reports explore this question in detail, with a particular focus on those aspects of climate change that will have greatest impact on the crops currently grown in each region: West Africa, East Africa, and the Indo-Gangetic Plains (IGP). The studies tested General Circulation Models (GCMs) by having them predict already-observed climate conditions, in order to establish the reliability of future climate projections. The studies also tested how well the models perform at predicting how associated crops might grow under future conditions. The reports were produced by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) and the School of Geography and the Environment at Oxford University, and looks at the CCAFS program's target regions.

The influences and interactions that control the climate of the West African region are complex, and the study finds that models have difficulty simulating already-observed climate changes, which implies that model projections of the future are highly uncertain. The East Africa study finds significant uncertainty as to changes in severity and frequency of extreme events, which could have substantial impacts on crop yields and food production. In the IGP region, there were marked contrasts between scenarios for locations suitable for cultivation of key crops for food and livestock feed in irrigated vs. rain-fed situations.

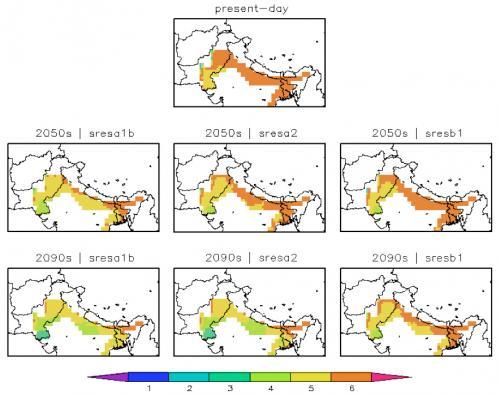

Within the IGP, it is critical that temperatures remain within a certain range to ensure successful harvests. For example, wheat requires different temperatures at different stages of its growth and development for optimum yields. In general, temperatures need to fall between 3.5 – 35 °C, with the optimum temperature being between 20 – 25 °C. Below or above the optimum temperature, seed germination decreases. Much of the IGP currently experiences temperatures in this optimum range for six months of the year, but rising temperatures may reduce many areas to five, four, or even just three months within the temperature thresholds (see Figure 1). These changes could have significant impacts on wheat yields and productivity across the IGP.

As well as testing the models individually, the researchers ran the models together to see how well they performed as an ensemble. This test produced varied results for the three future climate scenarios selected for evaluation. As shown in the figure below, the A2 high emissions scenario (characterized by independently operating nations; a continuously growing population; and regionally oriented economic development) gives the most dire projection of months suitable for wheat production in the IGP. By the 2090s, the projections of the medium emissions scenario, A1B (population reaching 9 billion in 2050 and then gradually declining; balanced emphasis on all energy sources), are similar to the A2 scenario in the reduction of suitable growing months. The low emissions scenario, B1 (population trend as in A1B, introduction of clean technologies, and environmental stability), shows the least reduction in the number of suitable months compared to the current climate.

The figure illustrates the type of projection the ensemble of models can produce. It shows projected changes in areas suitable for wheat (assuming irrigation is available) in the IGP. Without irrigation, the area suitable for wheat production in IGP is projected under all three scenarios to decline by 27% by the 2090s (see Figure J1 in Climate Change in Indo-Gangetic Agriculture: Recent Trends, Current Projections, Crop-Climate Suitability, and Prospects for Improved Climate Model Information). These results indicate that heat stress in the key staple food crops will be a major issue in the medium and long term. Consequently, research and action in this region could focus on finding ways to reduce, or deal with heat stress issues.

The reports highlight the considerable variability between models and between scenarios of future climate predictions. For example, the trend of annual mean temperature in the IGP varies greatly depending on the scenario used. Variability between models for rainfall projections is even greater than that for temperatures. But uncertainty is not an excuse for inaction. In fact, uncertainty of future predictions tells us that countries need to build adaptive capacity to support agricultural communities to adjust to the changing climate as it unfolds, and be prepared for a range of possibilities.

The reports also highlight how the models, despite their individual weaknesses, can be used together to produce useful climate projections. By using an ensemble of different climate models it is possible predict potential future changes such as shifts in crop suitability.

“Ensemble model predictions can overcome many of the individual model weaknesses to help decision makers plan future agricultural activities,” said Dr. Philip Thornton, who coordinated the research for the CGIAR Climate Change program, and based at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). “This information can guide investments in risk management, adaptation and mitigation research, as well as infrastructural development. These actions are crucial if agriculture is to adapt to a changing climate."

Browse and Download the Reports

Watch a recorded video seminar from the report's authors

Read more about our work on Data and Tools for Analysis and Planning

Read related stories on our blog

Laura Cramer is a Program Specialist for CCAFS East Africa Regional Office, based at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi, Kenya.