Big Facts: Focus on Food Security

This story spotlights some of the Big Facts on food security in a changing climate, and is part of a month-long series that complements the new Big Facts infographics website.

It is clear that the task of achieving global food security is facing several challenges from multiple fronts: growing populations, changing diets, and a need to make the food system more efficient, especially in terms of waste and distribution. Besides the demand for food, there are other non-food demands competing for agricultural products including biofuels, fibre, industrial uses, cosmetics, and luxury consumption items like alcoholic drinks, coffee, recreational drugs, and cut flowers. Of these, biofuels is increasingly the most important. In short, the world is steadily increasing its demand for food and food products in the coming decades.

A growing population – adding another two billion people to the world

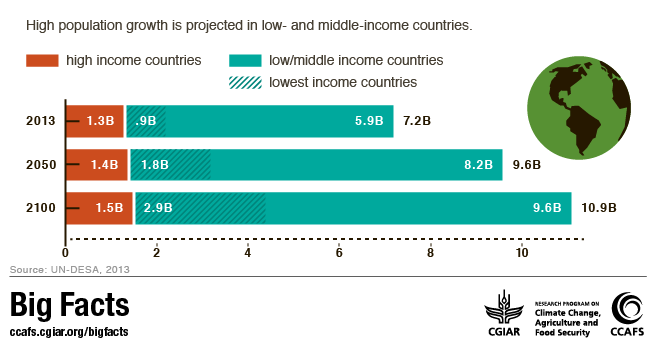

Population growth has stalled in many high-income countries and is even declining in parts of Europe. But most middle-income and low-income countries, particularly in Africa are growing rapidly. The current global population is 7.2 billion, with about 1.3 billion living in high-income regions. In 2050, the world’s population is expected to be around 9.6 billion, reaching 10.9 billion in 2100, according to the United Nations medium-projection variant.

The total population of today’s low- and middle income countries is projected to rise from 5.9 billion in 2013 to 8.2 billion in 2050 and to 9.6 billion in 2100. Growth is expected to be particularly dramatic in the least developed countries of the world -- countries already facing threats to food security. The population of these countries is projected to double in size from 0.9 billion in 2013 to 1.8 billion in 2050 and to 2.9 billion in 2100 (UN-DESA, 2013).

Fat or starved – an unequal distribution of food globally

The current distribution of food among populations is highly inequitable. The outcome is that 842 million people are undernourished and almost two billion suffer from micronutrient deficiencies (FAO, 2013). At the same time, more than 1.4 billion people are overweight. In 2008, 35% of adults aged 20 and over were overweight, and 11% were obese (WHO, 2012). And for those nations experiencing a growing middle class, it is not uncommon to see a high percentage of obese and undernourished within the same country or region.

Fat and processed – changing dietary preferences

Although very unevenly distributed, global average food consumption is increasing on a global scale – from 2,250 calories per person per day in 1961 to 2,750 calories in 2007 to a projected 3,070 calories by 2050.

It is assumed that by 2030, only Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia will have a mean daily caloric intake per capita of less than 3,000 (Kastner et al 2012; Alexandratos and Bruinsma, 2012: 50).

Globally, consumption habits are shifting towards diets containing more animal products and sugar. Demand is highest in high-income countries, where about a third of the diet consists of animal products, and it will remain so for the foreseeable future.

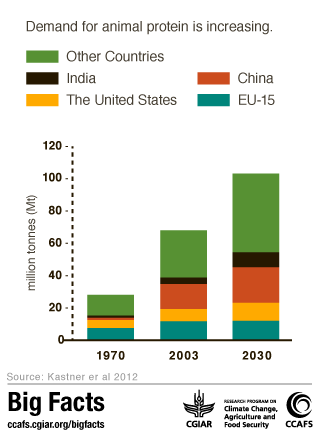

As meat consumption increases per capita, global consumption of animal protein has more than doubled since 1970, and is projected to increase another 60% by 2030.

However, this is still a modest increase compared to what would happen if the projected global population of 9.6 billion people in 2050 were to consume meat and dairy at current North American and European levels: the production of animal protein would have to more than triple! (PBL, 2009)

Wasting away

The most shameful part of our current food security situation is the amount of waste taking place. Avoidable food waste (that is, excluding non-edible parts such as skins and shells) amounts to about one-third of all food produced, about 1.3 billion metric tonnes per year. In high-income countries, most food waste is post-consumer waste; in low-income countries, most food is wasted on farm and in post-harvest storage and transport.

The most shameful part of our current food security situation is the amount of waste taking place. Avoidable food waste (that is, excluding non-edible parts such as skins and shells) amounts to about one-third of all food produced, about 1.3 billion metric tonnes per year. In high-income countries, most food waste is post-consumer waste; in low-income countries, most food is wasted on farm and in post-harvest storage and transport.

The greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated in the production and wastage of this food contributes about 6-10% of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions (Gustavsson et al., 2011; Vermeulen et al., 2012) and results in a loss of about 250 km3 of water, which is equivalent to the annual water discharge of the Volga river, or three times the volume of lake Geneva. About 1.4 billion hectares of land – 28% of the world’s agricultural area – is used annually to produce food that is lost or wasted. This is a size of land the size of Canada and India put together, and dwarfed globally only by the size of Russia (1.7 billion ha), and wasting all this food costs some $750 billion annually to food producers.

There are numerous options to reduce this waste, from policies to economic incentives to public awareness campaigns, to improving infrastructure for food transportation, processing and storage. The effectiveness of the various options will depend heavily on the context – policies that work well in some countries or regions will not necessarily be effective in other places. In some high-income countries, cutting domestic and retail food waste, perhaps through information campaigns or economic incentives, is important, while in low-income countries, policies to support infrastructure development could help reduce food waste (FAO, 2013b).

More food is needed, but how much?

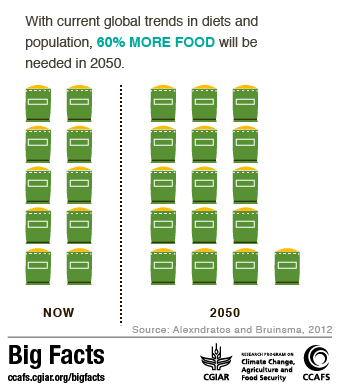

If there are no changes in waste and distribution of food among consumers, global agricultural production needs to increase by 60-100% between 2005/07 and 2050 depending on the projections used. This number could of course be lowered if food waste is reduced, but would need to be increased if other demands, such as biofuels or meat, increase, as biofuels may divert grains away from food production.

Currently, maize, rice, wheat, and soybean show yield increases of 1.6%, 1.0%, 0.9%, and 1.3% per year, respectively. At these rates global production of these crops would increase by ~67%, ~42%, ~38%, and ~55% in 2050, respectively (Ray et al., 2013), which is around the 60%-mark in some cases, but significantly below the doubling (100% increase) foreseen by some. A simple calculation like this shows that yield increases alone will not lead to food security in 2050, but must be coupled with other measures, such as increased efficiency in supply chains, less consumption of meat and dairy in some regions, and reduction in food waste, especially by consumers in high-income countries.

Furthermore, these figures are based on current growth rates and do not take into account the negative impacts of climate change on these crops. Rosenzweig et al (2013) assessed the impact on climate change on agriculture using five different Global Circulation Models to predict future climate impacts. The findings indicate strong negative effects of climate change on agricultural production, especially at higher levels of warming and at low latitudes. The current yield growth rates are therefore less than certain, and especially adaptation, another Big Facts topic, will be important to maintain yield increases.

Furthermore, these figures are based on current growth rates and do not take into account the negative impacts of climate change on these crops. Rosenzweig et al (2013) assessed the impact on climate change on agriculture using five different Global Circulation Models to predict future climate impacts. The findings indicate strong negative effects of climate change on agricultural production, especially at higher levels of warming and at low latitudes. The current yield growth rates are therefore less than certain, and especially adaptation, another Big Facts topic, will be important to maintain yield increases.

This is just a snapshot of some of the key Big Facts related to food security, and by no means an exhaustive list of topics. Please go ahead and explore the other findings in the food security infographic, as well as in related background documents. If you should need more information than what can be found in the graphic or the facts, a list of references and suggestions for further reading is provided at the bottom of each background page (hint: click "Explore food security" to access the pages). This list should satisfy even the most knowledge-hungry visitors.

Now you can get all the Big Facts on the links between climate change, agriculture and food security at ccafs.cgiar.org/bigfacts2014. The new site features over 100 stunning infographics that illustrate the most up-to-date, thoroughly researched information on these topics.

Big Facts is also an open-access resource. You can download and share the graphics with your friends and colleagues and use them in your presentations and reports. Please do not hesitate to send us any suggestions for improvements, either by commenting below or sending us an email.

This story is part of a series focusing on the Big Facts on various topics and in different regions; join the conversation at ccafs.cgiar.org/blog and on twitter using #bigfacts