Towards estimating the baseline: advances in the design of the coffee NAMA in Peru

Researchers support the design process of the coffee NAMA in Peru.

Since the official launch of the proposal at COP20, the coffee NAMA has become a strategic part of the Peru's climate commitment expressed in their National Determined Contributions (NDC) submitted to the COP21 of Paris in 2015 and also an element recognized in national strategic documents such as the National Strategy for Forest Conservation and Climate Change enacted in 2016.

The Peru coffee NAMA: why and how?

The country's need to have a NAMA for the coffee sector arises from the importance this crop has nationwide, considering that approximately 425 thousand hectares are devoted to this crop, besides it is the biggest crop in the Amazon (occupies 25% of the agricultural area) and is strongly linked to deforestation in the region, which is responsible for high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

In Peru, the coffee NAMA seeks to promote sustainable growth of coffee productivity through 1) the application of good practices that include agroforestry and proper management of fertilizers, 2) reducing emissions by avoiding deforestation and establishing or renewing the coffee production systems in fallow or degraded areas, and 3) reducing the emissions generated in the stages of processing and transporting the product.

Estimating the baseline

With the support of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the researchers Valentina Robiglio and Marta Suber from the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) have supported the design process of the Peruvian coffee NAMA team led by the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (Minagri) of Peru.

The researchers have articulated the different stages of estimating the baseline in the framework of a participatory and inclusive process of co-learning. They have undertaken a rigorous compilation of scientific and technical literature, were given industry expert information, collected qualitative and quantitative and national statistical data, and received contribution at each stage from organizations and national associations such as the National Coffee Board, SCAN Peru, Peruvian Chamber of Coffee and Cocoa, as well as non-governmental organizations like Rainforest Alliance, Solidaridad Network and Soluciones Prácticas, who provided information and validation of the process.

In two successive workshops co-organized by CCAFS-ICRAF, Soluciones Prácticas and Minagri, with the participation of about 40 coffee experts from different organizations and fields, Valentina Robiglio and Marta Suber presented concepts, stages and validated the assumptions of the different components that influence the GHG balance of the sector.

Valentina Robiglio (left) and Marta Suber (Right) in the first national workshop for establishing the baseline of the Coffee NAMA. Photo: E. Chavez

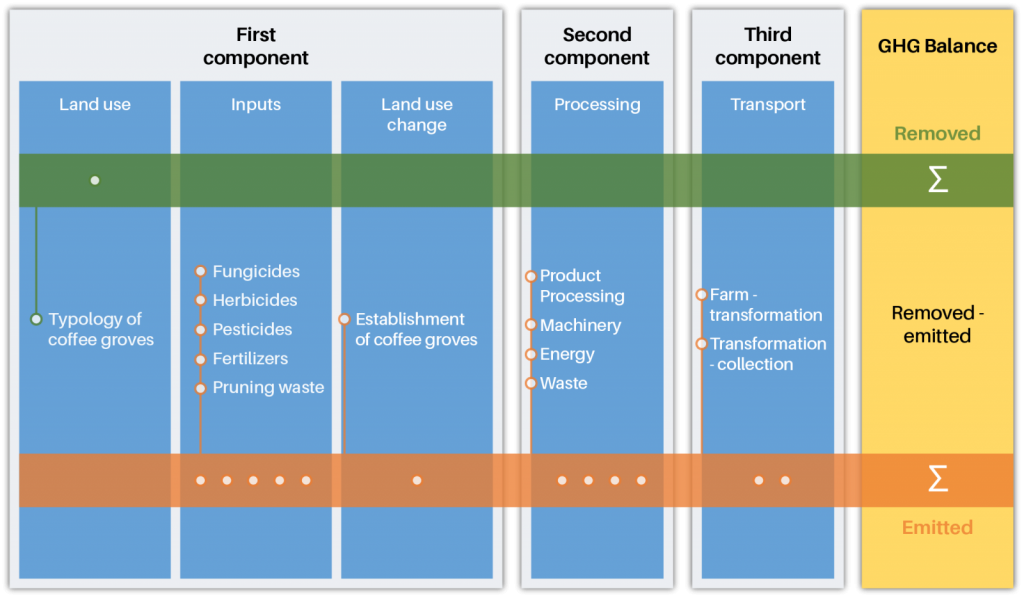

The methodology was to identify, distribute and estimate emissions of three components: (1) Land use and land use change and forestry (LULUCF), (2) Processing and (3) Transport.

Balance of emissions / removals coffee sector by NAMA-COFFEE with a breakdown of the components considered (Graphic: ICRAF)

Balance of emissions / removals coffee sector by NAMA-COFFEE with a breakdown of the components considered (Graphic: ICRAF)

The first component includes both carbon storage for land use and its relation with different types of coffee plantations, and emissions from the establishment of coffee groves according to the change of land use affected by such activity. Also, they consider GHG contributions in pruning waste management, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and fungicides.

The second component relates to emissions in the stages of product processing, including, where possible, materials, machinery and type of fuel used, and the waste and its management.

Finally, transport is accounted in two parts: between the farm and the collection point, and between the point of collection and processing sites for the parchment product. Accounting considers the distances, types of vehicles, the necessary material for travel and transport of the product.

What are the main sources of emissions in the coffee sector in Peru?

At the end of the process, the researchers presented a GHG baseline, identifying both the sources of emissions in absolute and relative terms per kilo of coffee produced, and business-as-usual scenario with a projected emissions by 2024.

The key role of land use change was highlighted as the main emitter by the continuous process of expansion of coffee crops in the forest, followed by the component of transformation in which waste, and specifically, the wastewater as a source methane (CH4) is the component that more contributes to emissions. Transportation, which had been underestimated in the environmental impact, was described by substantial emissions due to the use of polypropylene bags, material derived from fossil fuels. The importance of these emissions is a remarkable result itself, but, compared to the contributions of the other ingredients, of limited relevance.

GHGs generated by a unit of product indicate an average of 20 kilograms of carbon equivalent per kilo (kgCO2e/kg) of coffee, and the trend is that this will increase in time. These values depend on the practices of establishment of coffee plantations, for example, the land replaced for the cultivation and the level of shade that determinate the system's ability to store carbon, among others.

Mitigation options available are well linked to the implementation of agroforestry systems. The conversion of coffee plantations in complex agroforestry systems, recovery and installation in degraded areas, renovation of coffee plantations and the use of fallow areas, while increase the capacity to store carbon and reduce the expansion of cultivation in forest areas, strongly reduce emissions of this component.

Business-as-usual projection indicates an increase in annual emissions to about 10 MtCO2e in 2024, which is the double of the average emissions from 2004-2015 season. Consideration of production systems and their trajectories concerns identifying strategies, policies and actions to be implemented to reduce the impact that these entail for the environment.

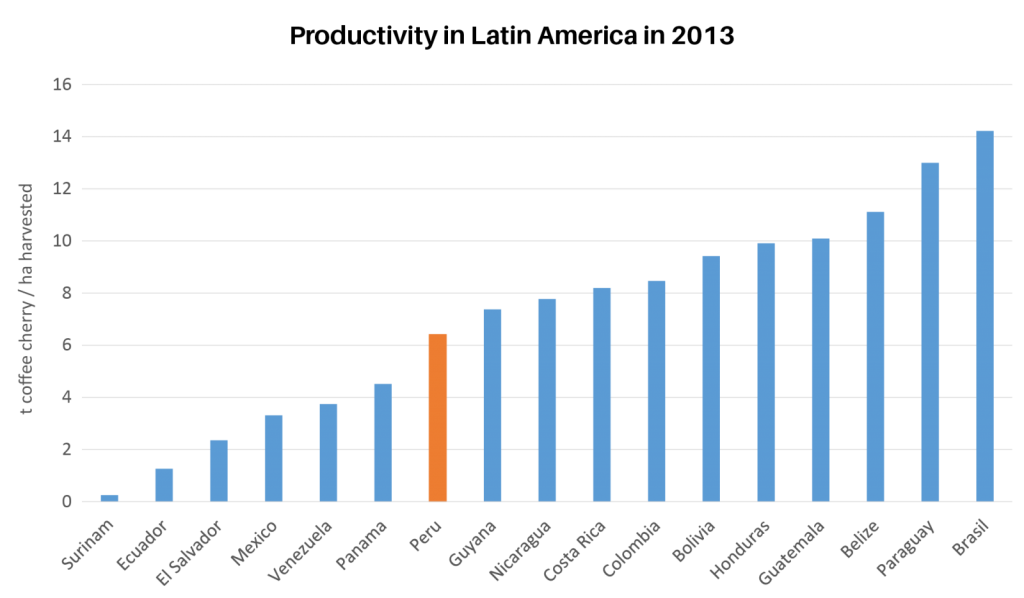

Another key issue in reducing emissions by land use change is to increase productivity, which currently is below 7 q/ha (FAOSTAT 2013) and lower than in other producer countries in Latin America such as Brazil, Guatemala, Honduras and Costa Rica (14, 10, 9 and 8 respectively, FAOSTAT 2013).

Source: compiled from FAOSTAT 2013

Few producers use inputs and that keep down its emissions quota. Still, proper handling to avoid waste and overdose in applications, calibrated according to crop needs, production season and soil characteristics and production system itself, represents a valid measure of emission reduction for the sector, which is important as Peru ranks second in production and export of the global organic coffee market.

Key messages and next steps

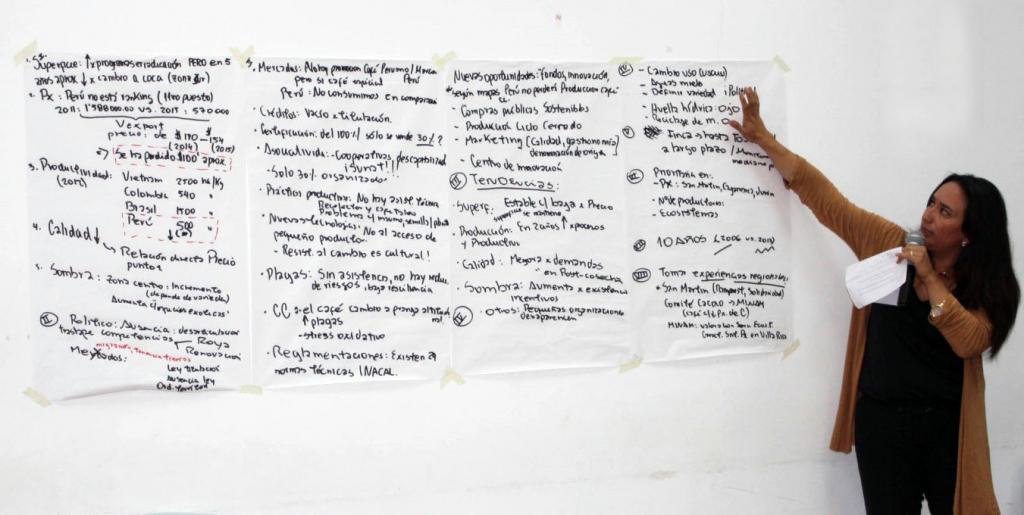

Results of the analysis of barriers to the development of the coffee by the group of political experts, in the first national workshop NAMA-COFFEE sector. Photo: E. Chavez

In addition to typical interventions in reducing emissions in the coffee sector like the treatment of the wastewater, reducing nitrogen fertilizer and promotion of agroforestry systems are indicated in mitigation strategies of other countries. The key role of spatial planning with a landscape approach is evidenced, which through mechanisms and policies has the potential to establish an institutional, political and economic framework that discourages land use changes and deforestation, and encourages the renewal of areas already cultivated or fallow land and recovery of degraded areas.

To complete the design of NAMA, it is now necessary to identify priority areas of intervention and define the activities that will be implemented.

See the image gallery of the workshop

Valentina Robiglio y Marta Suber are researchers of the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF).

Edited by José Luis Urrea, Communications Officer for CCAFS Latin America.