What will it take to spark the climate-smart revolution?

In climate-smart agriculture, "the action is at the local level," according to Lindiwe Sibanda, who moderated a high-level panel on this topic at the recent CGIAR Development Dialogues. In a context-specific world, what role can global science play in sparking a rapid transition to a smarter agriculture?

As the international community moves to define goals for sustainable global development under a new climate reality, the launch of the Global Alliance on Climate-Smart Agriculture marks recognition that we cannot address climate change without taking on the role of agriculture.

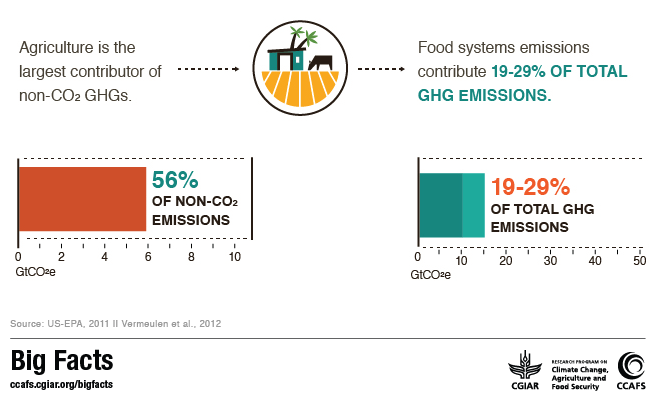

Agriculture is at the heart of sustainable development: it is livelihood of hundreds of millions of people in developing countries, and a vital part of countries’ economies. It also contributes to a large share (19-29%) of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Productivity must increase by 60% to feed 9 billion by 2050, while curbing impacts on the environment. At the same time, agriculture has to adapt to survive higher temperatures and more flooding, drought, and extreme storms.

Productivity must increase by 60% to feed 9 billion by 2050, while curbing impacts on the environment. At the same time, agriculture has to adapt to survive higher temperatures and more flooding, drought, and extreme storms.

The productivity gains of the past fifty years came at the expense of ecosystems and the climate, and we now know that agriculture needs to transform to face a new climate reality. What will it take to spark a rapid transition to a smarter agriculture?

A new climate reality

The CGIAR Development Dialogues, held during Climate Week surrounding the UN Summit, engaged scientists and policymakers around the role of agricultural science in revolutionizing how we feed the world.

One of the high-level panel sessions at the Dialogues examined climate-smart agriculture, which offers a way forward towards three goals: near-term productivity and food security; longer-term resilience and adaptation to climate change; and reductions in emissions across landscapes, agriculture and food systems. The climate-smart approach encompasses a suite of technologies and practices that are implemented and adapted to the local context by farmers, with the help of researchers, policymakers, extension agents and other partners.

Watch the video of the session - Climate-smart agriculture: balancing trade-offs in food systems and ecosystems

Scientists in the dialogues session spoke to the potential for tradeoffs between environmental sustainability and productivity gains, and outlined the role of science in targeting a new climate-smart agriculture to local contexts across the globe.

The largest environmental trade-off with food production is deforestation, noted Cheryl Palm of Columbia University—but the trend is moving downward, thanks to cooperation among governments, the private sector, and scientists.

Another major environmental tradeoff with food production is nitrogen fertilizer usage, she said, but science has shown that in systems with too much nitrogen, yields can stay stable or increase while using less. In turn, in systems with too little nitrogen, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, using more fertilizer can increase yields without affecting greenhouse gas emissions.

Ready for roll-out

The climate-smart approach puts forth the idea that technologies are available today that can increase production while improving management of climate risks, adapting agricultural systems to longer-term climate change, and reducing emissions.

But farmers’ adoption of improved technologies in complex smallholder systems is a major challenge. Small farmers in the developing world lack the capital to invest in improved technologies, and are inherently risk-averse because their resilience to shocks is low. CGIAR research shows that technology adoption rates among smallholder farmers in developing countries is low (e.g., Thornton and Herrero, 2010). How can we tackle the adoption challenge for climate-resilient practices and technologies?

Dr. Palm spoke to the role of agricultural research in linking biophysical systems with socio-economic factors that determine where climate-smart interventions make sense, and urged a stronger focus on adoption. Science can tell us where it makes sense to target interventions, bringing technologies down to the local level—but these interventions will only make an impact if they are used by farmers and decision makers.

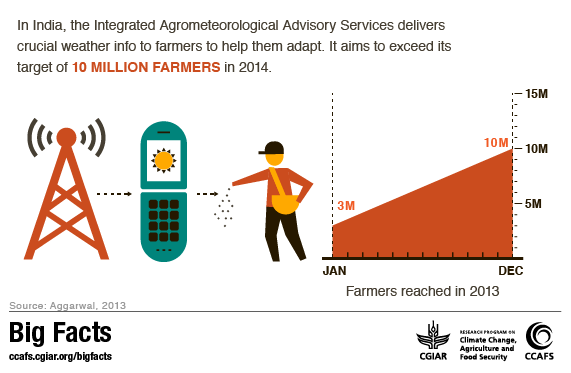

New research from the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security suggests that we can break the pattern of low adoption by farmers. The rapid spread of information and communications technologies in rural areas is primed to bring smarter solutions to farmers’ fingertips. In Senegal alone, the national meteorological service is using community radio to deliver climate forecasts to over two million farmers. India's Agrometeorological Advisory Service reaches over 2.5 million farmers (as of 2012) with agro-climate advisories using SMS and interactive voice messaging.

The climate-smart approach emphasizes reducing risk to make productivity-enhancing, climate-resilient technologies more accessible. In particular, weather index-based insurance is designed to remove weather and climate risk from the equation, allowing farmers to safely invest in productivity-enhancing technologies. In India, 30 million small farmers are already insured with policies that pay out when growing conditions are bad.

Science as communicator

In the global transition to a smarter world, the choices that we make are inherently political. Science can play the role of an ‘honest broker,’ the panellists agreed, between policymakers and the practice communities—farmers and the private sector. Science informs policy, but at the same time it is based on practice, said Dr. Youba Sokona of the South Centre.

Engagement with the users of research—policymakers, farmers, and the private sector—is one of the best investment bets for science, said Dr. Marion Guillou of Agreenium. Partnership with national, regional, and local institutions, and farmers themselves, can identify what needs to be in place to make climate-smart technologies work. Sharing this knowledge widely, along with capacity development and capacity mobilization to put technologies in motion, is another area of strength for agricultural science.

Ultimately, adoption of climate-smart technologies is a question of context. Agricultural research can help us move beyond understanding of the biophysical systems that make technologies climate-smart, to an appreciation of the institutional and socioeconomic context that makes their adoption possible in a given place.

After all, as moderator Lindiwe Sibanda summed it up, in climate-smart agriculture, "the action is at the local level."

The panel session was co-organised by CCAFS, and the CGIAR Research Programs on Water Land and Ecosystems (WLE) and Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA)

Session moderated by Lindiwe Sibanda, CEO and Head of Mission, FANRPAN

Panel members:

Marion Guillou, Chair, Agreenium, Board Member, CGIAR Consortium

Cheryl Palm, Director of Research in the Agriculture and Food Security Center of Columbia University

Youba Sokona, Special Advisor on Sustainable Development, The South Centre

This post is part of a series related to Climate-Smart Agriculture at the UN Climate Summit. Get a full rundown of Climate-Smart Agriculture events at Climate Week NYC and follow updates on our blog and via twitter @cgiarclimate. Learn more about Climate-Smart Agriculture and Climate-Smart Villages.