Spilling the beans: Peru's coffee value chain in a changing climate

A new in-depth study looks at what Peru’s coffee value chain can and must do about climate change.

Climate change will affect Peru’s northeastern coffee region across all links in the crop’s value chain, though primary production will be impacted most significantly, according to a recent study from the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).

The study analyzes the vulnerability of the coffee value chain in the face of climate change and the adaptive capacity of its actors in the Amazonas, Cajamarca and San Martin regions. The study, part of the Café y Clima project for Peru’s National Coffee and Cocoa Chamber, has been supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

With climate change creeping in, it is estimated that more than 30% of the current producing areas in Peru’s northeast will have to adjust their production systems fundamentally, as they might no longer be suitable to grow coffee by 2030. “This is a major concern for the sector, as well as for society, since departments in the northeast are responsible for more than half of Peru’s coffee production, coming from 185,000 smallholder families,” says Valentina Robiglio, project coordinator from ICRAF. “These farmers are most directly exposed to climate change effects, which worsen the daily challenges they are already facing.”

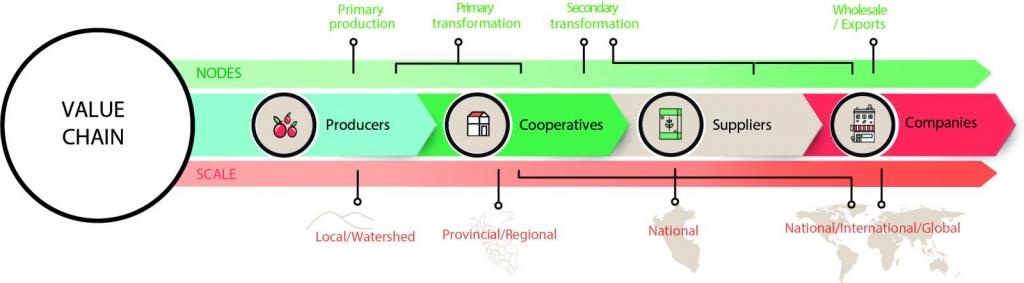

What happens in primary production creates a ripple effect across coffee’s value chain, where alongside producers there are local middlemen, farmers’ cooperatives and associations, and private companies, as well as public institutions and agencies.

How much producers are and will be able to adapt to climate change will depend on: access to seeds, information and technology, use of agro-forestry systems, good practices and experience in adaptation. Photo: Neil Palmer

The study focuses on vulnerability as a function of exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity.

Apart from those areas that might need to find alternatives to coffee production, as they will get too hot and dry (below 1000 m), large areas in Amazonas, Cajamarca and San Martin will not go through major changes, but will need to increase productivity. Coffee might also find space to expand at higher altitudes (2500-3000 m), as climate conditions transform. The highly productive areas where the future is still uncertain—between 1000-2000 m—will have to find resilience mechanisms at system level to maintain their productive capacity.

Low and medium altitude areas are more sensitive to climate change-related risks, with the study pointing out a higher variability of production capacity, quantity and quality, and reliance on coffee for farmers' food security and livelihood. The highest sensitivity however, is related to pests and diseases, with producers reporting massive negative impacts after coffee rust outbreaks.

Climate change impacts will be aggravated by poor crop management that already undermines the present production—in some cases, farmers do not know what their soils need, they do not fertilize properly, they lack technical assistance and their aging plantations are already deeply bruised by coffee rust.

The farmers themselves are highly sensitive to future climate change, especially if their food security depends on income-generating coffee production. Between October and December, small coffee producers do not have enough money for a diversified diet, and rely mostly on yucca and rice.

Producers’ adaptability depends on: access to seeds, information and technology, use of agro-forestry systems, good practices and experience in taking adaptation measures. But the present situation does not look that bright: “Getting access to credit to purchase fertilizers at an appropriate time and quantity, and to cover production costs throughout the year, is not a given for many farmers,” says Robiglio. “No wonder productivity is low and cup quality has been going up and down across the years.”

And while producers’ level of association in these areas is high compared to national levels (about 50%), that does not mean it works effectively—they receive too little support to really introduce innovations, as only a small number of farmers have access to the technologies they get to learn about. As they are short on money, they use the credits they get for short-term remedies, not for adaptation measures or diversifying. With many farms below 10 ha, very few have enough land to set aside for protecting and recovering ecosystem services.

A simplified coffee value chain, showing interaction across scales. Source: ICRAF

“Our work is providing support to stakeholders for a planned change process instead of spontaneous shifts as a result of catastrophic events,” says Christian Bunn, leading researcher on climate change impacts on coffee at CIAT and main author of the study. “The climate change discussion is often limited to farm level impacts, with little research on what elements it will affect down the supply chain.”

Farmers’ associations and cooperatives will also have a hard time adapting, as they lack income and support from private and public entities, and they are also short on information regarding how climate change will affect coffee in the region. And while companies in the coffee business are more able to adapt, as they have the capital to stimulate local economies and manage risk, they still need governmental support to take adaptation and mitigation measures.

The value chain vulnerability coincides with the lack of support for primary production, the researchers point out. Many of these weaknesses are already known and take effect independently of climate change. The ICRAF-CIAT study uses climate change scenarios to understand its potential impact. It is news however, that under these scenarios the entire coffee sector needs to coordinate and react together and promptly, if it is to stand up to its future. In the words of Bunn:

Adaptation to climate change will be a complex task that requires every stakeholder to think outside the box. There is not a single solution that solves all issues and farmers will do what is within their power to manage risk. They’ll have to be provided with the means to help themselves, but this requires change on several levels along the supply chain.”

Alexandra Popescu is the Communications Officer for CCAFS Latin America.