Global carbon tax would increase undernourished by 80-300 million; alternative strategies protect food security

Given the need to limit global warming to less than 2 °C, new research analyzes how climate change mitigation in the agriculture sector may impact food production and food security.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture without compromising food security?

Research published this week in the journal Environmental Research Letters examines mitigation policy scenarios in the agriculture, forestry and land use sector that would help stabilize climate change to less than a 2 °C increase in global temperature and how they would influence food security. It is one of the first studies to examine the effects of countries’ participation in mitigation, particularly the different roles of developing, emerging and developed countries.

Scientists from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) explored how a global carbon tax together with land-based climate change mitigation options would affect the cost of major food commodities. To do this, they used established climate stabilization scenarios for achieving 2 °C with the Global Biosphere Management Model (GLOBIOM), a partial equilibrium model that considers both biophysical and economic changes.

Uniform global carbon tax will not have uniform effects

A widely discussed cost-efficient mitigation policy is a global tax on carbon. Research shows that a USD 10 tax / ton of carbon dioxide equivalent would achieve some mitigation cost-efficiently, and thus not raise food prices significantly. However, a higher carbon tax such as USD 100/ton – which would be necessary if the global community employed carbon taxes as a principle mitigation tool – would cause steeper food price increases, in large part because of the wide extent of inefficient food production practices and the cost of shifting from these practices to more efficient production. Higher food prices would lead to more food insecurity and undernourishment in some countries.

Researchers estimate that a uniform carbon tax could increase the number of undernourished people by 80 to 300 million in 2050.

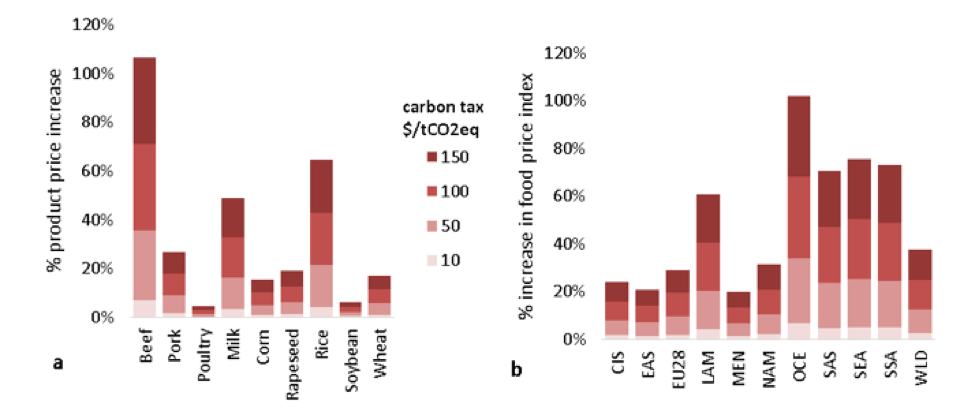

(a) Relative price impact of a carbon tax (0 – 150 $/tCO2eq) on emissions from agriculture on global commodity prices and (b) regional food price index.

These calculations assume no shifts in production to more emission-efficient systems, so may overestimate price impacts. Guide to abbreviations: CIS – Commonwealth of Independent States, EAS – East Asia, EU28 – European Union, LAM – Latin America, MEN – Middle East and North Africa, NAM – North America, OCE – Oceania, SAS – South Asia, SEA – South East Asia, SSA – Sub-Saharan Africa. WLD - World. Source: Figure 1, Frank et al. 2017)

Researchers found that the carbon tax would raise the price of most food commodities, but most significantly in emission-intensive beef, rice, and milk.

While food prices would increase across the globe, prices would increase the most in Oceania, Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia due to emission-intensive agricultural production, emission-intensive diets, or both.

Achieving climate change mitigation while protecting food security

A diverse portfolio of ambitious low emissions development practices, policies and economic measures is needed to achieve food security, as described in the Environmental Research Letters paper and a related info note, titled 'Carbon prices, climate change mitigation & food security: How to avoid trade-offs?'

Global cooperation, a diverse mitigation option portfolio, and win-win options, such as possibly soil carbon sequestration, are key to achieve ambitious climate change mitigation targets without jeopardizing food security,” lead author Stefan Frank said.

Options in the food system include:

- soil organic carbon sequestration,

- reduced deforestation,

- sustainable intensification of agriculture,

- diet shift toward less emission-intensive foods,

- reducing food loss and waste, and

- improved technologies.

Policy and economic measures include:

- international trade mechanisms,

- climate finance,

- agricultural investment, and

- redistribution of a carbon tax.

While some land-based mitigation options will increase food prices, and therefore food insecurity, the study presents two strategies that can maximize benefits for the climate while maintaining food security: reducing deforestation and increasing soil carbon sequestration.

Regions that can reduce deforestation can mitigate with less cost to food security

The analysis described in the study found that reducing emissions from land-use change in land-rich countries has large mitigation potential and limited trade-offs with food security. For example, if developed countries and Brazil followed a cost-efficient mitigation regime, mitigation would be achieved through avoided deforestation and have little impact on agricultural production. Conversely, mitigation in densely populated countries with intensive agriculture would likely lead to more significant decreases in agricultural production and resulting increases in food insecurity.

Soil organic carbon sequestration offers a potential we must pursue

Humans can increase soil organic carbon through cropland and grassland management, biochar application, enhanced biomass in roots, and restoration of degraded lands and organic soils – and such efforts most often also improve soil productivity and water storage.

Researchers are investigating how to scale up soil organic carbon sequestration and its benefits for soil health, resilience, and food security.

Scenarios resulting from the GLOBIOM model, presented in the article and the info note, 'The potential of soil organic carbon sequestration for climate change mitigation and food security,' estimate that soil organic carbon has the potential to sequester up to 3.5 GtCO2eq/yr by 2050, helping the world limit global warming to 1.5 ºC warming. SOC sequestration potential in 2050 could offset approximately 7% of total 2010 emissions.

Scenarios resulting from the GLOBIOM model, presented in the article and the info note, 'The potential of soil organic carbon sequestration for climate change mitigation and food security,' estimate that soil organic carbon has the potential to sequester up to 3.5 GtCO2eq/yr by 2050, helping the world limit global warming to 1.5 ºC warming. SOC sequestration potential in 2050 could offset approximately 7% of total 2010 emissions.

Soil carbon has the potential to minimize food price increases, potentially protecting the food security of up to 225 million people.

Soil carbon sequestration is indispensable to achieve ambitious climate change mitigation targets with optimal cost-efficiency and tempered impacts to food security,” the study said.

Research:

- Frank S, Havlík P, Soussana J-F, Levesque A, Valin H, Wollenberg E, Kleinwechter U, Fricko O, Gusti M, Herrero M, Smith P, Hasegawa T, Kraxner F, Obersteiner M. 2017. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture without compromising food security? Environmental Research Letters. DOI:10.1088/1748-9326/aa8c83.

- Frank S, Havlík P, Valin H, Wollenberg E, Hasegawa T, Obersteiner M. 2017. Carbon prices, climate change mitigation & food security: How to avoid trade-offs? CCAFS Info Note.

- Frank S, Havlík P, Soussana J-F, Wollenberg E, Obersteiner M. 2017. The potential of soil organic carbon sequestration for climate change mitigation and food security. CCAFS Info Note.

More information:

- Low emissions development pathways project

- USAID and CCAFS collaboration on low emissions opportunities in agriculture

- IIASA

- Soil organic carbon sequestration initiative: 4P1000 and recent blog: 4P1000 receives Future Policy Vision Award from the World Future Council

- Research: Farm-scale greenhouse gas balances, hotspots and uncertainties in smallholder crop-livestock systems in Central Kenya

- Book chapter: Methods for Smallholder Quantifications of Soil Carbon Stocks and Stock Changes

- Video: Measuring soil organic carbon on smallholder farms in Ghana

This work was undertaken with support from USAID and CGIAR Fund and bilateral donors. IIASA also received support for this work from the European Union’s FP7 Project FoodSecure, the Belmont Forum/FACCE-JPI funded DEVIL project, UGRASS (NE/M016900/1), IIASA’s Tropical Futures Initiative (TFI), and the GCP’s Managing Global Negative Emissions Technologies (MaGNET) program.

Julianna White is program manager for CCAFS Low Emissions Development.