Ma Village maps land use to know viable agriculture options

In any development initiative, assessment of past and current local scenarios and conditions is important to effectively plan agricultural interventions.

In the mountainous region of northern Vietnam, Yen Binh district, province of Yen Bai, rests Ma Village, a community with 183 households who depend mainly on forestry and farming for their subsistence and income source. Nestled in Thac Ba Lake, a manmade lake, is the Thac Ba hydroelectric plant, the first in the country, for which the lake was purposely built for. Currently, village farmers cultivate cassava, maize, tea, and rice. Ma’s proximity to Thac Ba Lake enables aquaculture farming as well.

Due to the extreme changes in climate, the village has been experiencing cold and drought stress with more intense rains during rainy season and increased intensity of dry and hot weather. These climate challenges have been causing the decline in cereal yield, high death rate on forestry seedlings and fish, and soil erosion, thus, making prices of agricultural products unstable. Additionally, wood and cassava processing have also been contributing to environmental pollution.

These are some of the compelling reasons for establishing Ma Village as one of the three Climate-Smart Villages (CSVs) in Vietnam. With support from the CGIAR Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the Ma CSV would be the testing ground for climate-smart agriculture (CSA) technologies and practices as determined by the villagers themselves. The CSV approach hopes to improve the agricultural productivity and climate resilience of Ma Village, while reducing greenhouse gas emissions from its agriculture systems. The International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) leads the collaborative research initiatives with various stakeholders, putting premium on community involvement and participation.

A bit of history

CIAT organized and facilitated a workshop to establish the land-use history of the village with the help of a village elderly and two key farmers in the village.

A century-old village, the first sign of development happened during the 1960s with the building of Thac Ba Dam for the Thac Ba hydropower plant. It resulted in the relocation of many villages of three communes. But the people of Ma Village remained and resident households increased.

Due to increasing population, village people and farmers from neighboring villages started to clear the forest adjacent to paddy fields and forest areas toward Thac Ba Lake to make space for maize, sweet potato and peanut production. That time, the forest clearing was illegal because private production was not allowed during the collective period.

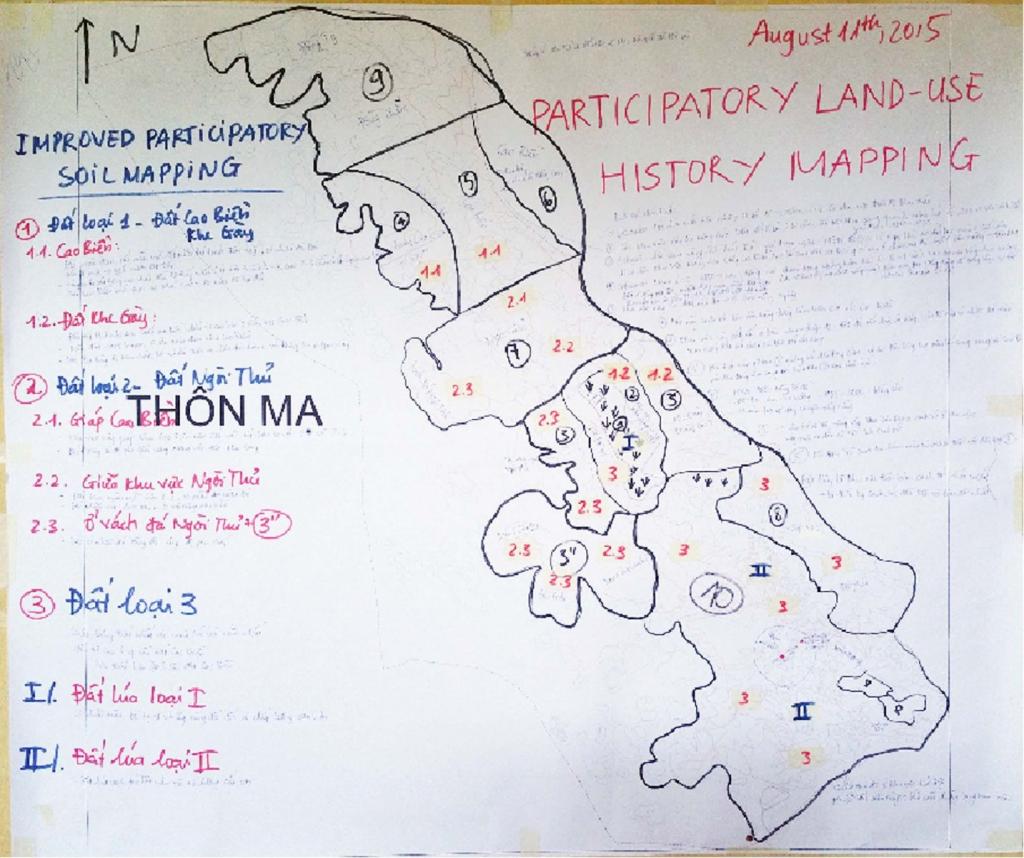

Complete land use history map of Ma CSV illustrating the evolution of farming systems and geographic coverage. Photo: VL Bui, CIAT

In 1971, the government set out a policy to develop tea plantations and industrial trees for oil production in homestead surroundings. The policy protected the forest temporarily. Forest protection was further reinforced when a paper company in Phu Tho province, a mere 60 kilometer southeast of Ma, created an increased demand for raw materials from trees. Tree plantations then expanded. While it provided income to village households, it likewise marked the start of widescale forest devastation.

Mapping the village with local people

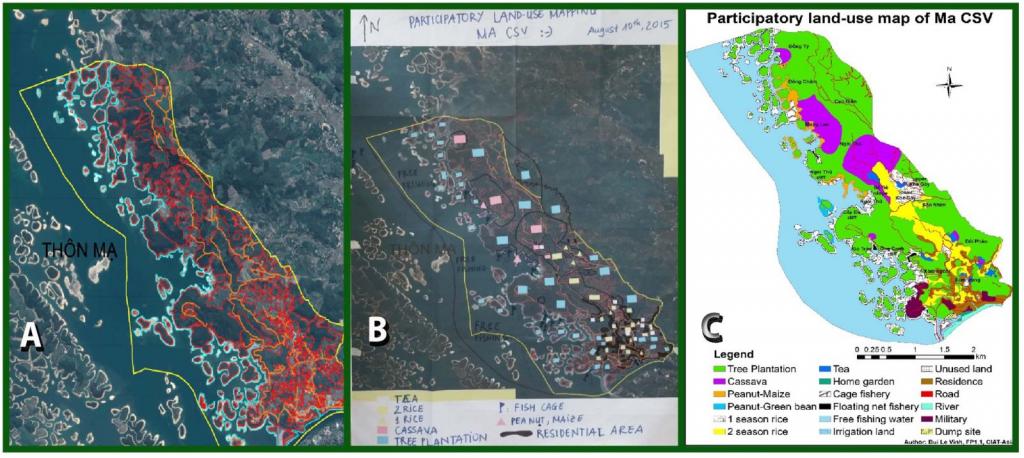

Like most remote districts in Vietnam, Ma Village does not have a cadastral map, which provides valuable information on boundaries, land ownership, different land-use types and soil quality for planning field trials and assessing crop suitability for climate-smart agriculture interventions in the village. Thus, Vinh set out to Ma Village once more to conduct a participatory land-use mapping.

CIAT, together with the leaders of the village, union of women’s group, village cooperative, and a village police man, mapped the community in three forms: land use, land-use history, and soil maps.

A digitized map image of the village was downloaded from Google earth, an internet-based program that provides virtual view of earth in high resolution graphics. Figures were overlaid based on visible boundaries and different color patterns of the image. Roads, rivers/ streams, ponds and lakes are highlighted on the map as key landmarks. Then, residential areas, paddy fields along the main valley and around village houses, and other village features were identified.

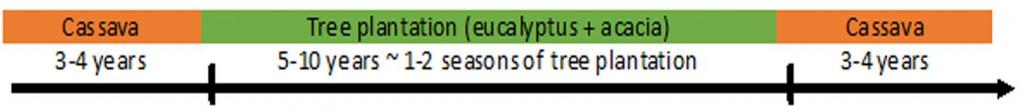

Upland crops were named next. Small tea plantations are found scattered around homesteads. Eucalyptus, acacia and cassava are the most important upland trees and crops. Based on the village baseline survey conducted previously, tree plantations occupy around 200 hectares of the village and cassava is about 100 hectares. Village farmers practice cassava-trees crop rotation, that is, cassava fields are often converted from tree plantations.

After 1-2 life cycles of trees (5-7 years per cycle), the soil would have recovered from soil erosion and degradation from previous intensified cassava cropping. After 3-4 years of intensified cassava farming, the land is converted again to tree plantation to restore soils from degradation. The key farmers state that the boundaries of cassava and tree plantations are just temporary and will change every year due to this crop-tree rotation scheme.

Ma CSV has about 500 hectares for fish farming. The farmers pinpointed on the map major areas for fish caging (including around 70 fish cages) and 3 floating nets, and fish farming in a larger area of water surface (3-5 ha) with a net that can float with increasing and decreasing water level.

Participatory land-use mapping is a useful approach and effective way of extracting information about the village especially without any detailed map resources available as in the case of Ma CSV. The process itself elicits active participation among the villagers and increases the likelihood that they would buy-in on current and future initiatives.

The progression of land-use map in Ma Village created by key people of the village: (A) digitized map overlaid with polygons to identify land-use types; (B) completed land-use map based on local knowledge; (C) digital version of the completed land-use map. Photo: VL Bui, CIAT

Read more:

- Community mapping in Vietnam: lessons learned

- Farmers in Southeast Asia learn about climate-smart agriculture practices

Vinh Le Bui is a soil scientist and research coordinator at CIAT Vietnam. Story edited by Bernadette Joven, Senior Communication Specialist for CCAFS SEA.