Will climate change make us go hungry by 2050?

New meta-analysis highlights that a significant increase in investment, policy and institutional support to agricultural adaptation can limit the challenge of climate change to food production till the 2050s.

May it be a lawsuit filed by 21 young plaintiffs against the United States or the call for a Green New Deal, masses are demanding for concrete action to curb climate change. The world is rallying together for climate action, from school strikes to public awareness campaigns. In the recently released BBC programme “Climate Change - The facts”, Sir David Attenborough highlights the future crisis the world will face if climate change is not tackled. With climate change threatening human existence, this uproar is very well understood; especially when humankind is already struggling for survival due to the lack of resources.

Globally, 844 million people lack access to clean water and around 821 million people in the world still lack sufficient food to live a dignified life. Unequal distribution of resources, social constraints, governance challenges and political limitations further add to this plight. In the future, vulnerabilities in agricultural production will exacerbate due to climatic changes. Warming temperature, changing rainfall patterns and extreme weather events are expected to reduce food production, while rising population will put pressure on the agricultural sector to meet the food demand of the world.

To better understand these vulnerabilities and streamline climate action, scientists have been trying to quantify this vulnerability of agriculture to climate change through impact assessments, since the 1980s. Periodic release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports have generated huge public interest and influenced policies globally. Many research studies have proliferated since then, quantifying projected climate impacts on agriculture at diverse spatial scales, using various climate and crop models.

Is adaptation a game changer?

Read the article here.

A recent publication has comprehensively summarized this large body of work—done over last 40 years—for the most consumed cereals globally (wheat, rice and maize), with important takeaways for food security. The authors analyzed more than 150 studies published since the 1980s, using meta-analysis technique. The results, highlighting high impacts of climate change on the productivity of rice, wheat and maize, with respective area-weighted global losses reaching up to minus 12%, minus 15% and minus 20% by 2080s, are pressing enough to rally the world to move towards adaptive measures.

Adaptive measures such as change in planting date, cultivating improved variety, increased nutrient and water application are known to dramatically decrease the negative impacts of climate change. The results after adaptation point out a much smaller net reduction in the productivity loss of rice (-6%), wheat (-4%) and maize (-13%) by 2080, if adaptive measures are employed. Adaptation also brings a level playing field for tropics and developing regions, by equalizing the impacts from climate change across different regions.

What does this mean for future food security?

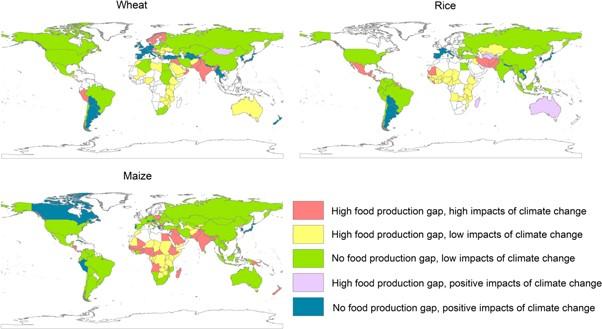

Implemented adaptive measures will lessen productivity losses. However, the paradox might be that global reduction in projected climate impacts after adaptation may invite complacency on the part of nation’s food security policies. It is crucial to understand that even such small impacts may have a disruptive effect on the global food supply. To underline this, the article identified global hotspots of potential food insecurity, by analyzing projected future food demand for the 2050s along with the national food supply. Consequently, most of Africa, South and Central Asia, along with temperate countries in South America and Scandinavia were found to be vulnerable due to both food production gap and the projected negative impacts of climate change.

These regions have immense food security problems. They have a two-fold crisis: a) their growth rate of food production already lags behind the projected demand and b) future climate change will further disrupt their food supply.”

Pramod Aggarwal, Regional Program Team Leader, CCAFS

Figure 1: Hotspots of climate change based on assessments of impacts after adaptation on crop yield at country scale for the 2050s and the food production gap (the difference between 2050 food demand and current food supply)

Where are we headed?

Impact assessments on agriculture underline the considerable potential of adaptation in moderating the negative effects of climate change. However, these processes are hard to implement and come with a cost.

These adaptation strategies are constrained by the economic, institutional and ecological costs involved. Massive science-guided investments and policy support is required to scale-out adaptation globally. Pathways to sustainable development like climate-smart agriculture may prove to be a more viable alternative than intensive agricultural practices.”

Bruce Campbell, Program Director, CCAFS

Read more:

- Journal article: How much does climate change add to the challenge of feeding the planet this century?

Sakshi Saini is a Communications Specialist for CCAFS South Asia. Shalika Vyas is a Research Consultant for CCAFS South Asia.