How organizations in CCAFS sites coordinate on climate change and agriculture initiatives

New paper analyzes agricultural policy development networks connecting various organizations to enhance understanding of their problem-solving potential.

To effectively increase food security and advance agricultural development under climate change, cross-scale public and private organizations need to coordinate with each other to provide resources and support to smallholder farming communities. Understanding which actors are involved, what resources they bring into the collaborative network, and how they engage with one another are critical to realizing the potential for networks to be effective in solving the problem at hand. In the contexts of food security and agricultural adaptation to climate change, collaborative governance networks have gained attention for their potential to leverage social capital, motivate coordination in crisis-response periods, and build community resilience.

A recent study, carried out by scientists from the University of California Davis, the University of Vermont, and the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) focuses on mapping the organizational networks that are present in the CCAFS sites and uses relevant characteristics to understand what network types actually exist in agricultural development contexts.

The study uses data from the CCAFS Organizational Baseline Surveys (OBS) and it is the first to use this particular data to characterize and explore how agricultural development policy networks vary across region and place.

Organizational network types

The modes of network governance framework differentiate networks that might be observed across communities in terms of centralized and decentralized structures, as well as what types of organizations might serve in leadership roles within these networks.

Generally, these can be classified into the following broad types:

| Brokered networks: highly centralized, hierarchical networks where a single actor sits between all, or nearly all, other actors, acting as a key partner in the majority of network activities. The central actor brokering these exchanges can be external to the community, or a lead organization that is embedded within the community. |  |

| Shared networks: decentralized networks with a high density of connections between almost all of the organizations. Responsibility for network activities can be shared across many organizations, and there is no single organization coordinating everyone. |  |

| Fragmented networks: many isolated actors that have few to no partnerships with other organizations. These networks have relatively low coordination between the efforts led by organizations acting independently from one another. |  |

Characterizing network structures across 14 research sites in 11 different countries

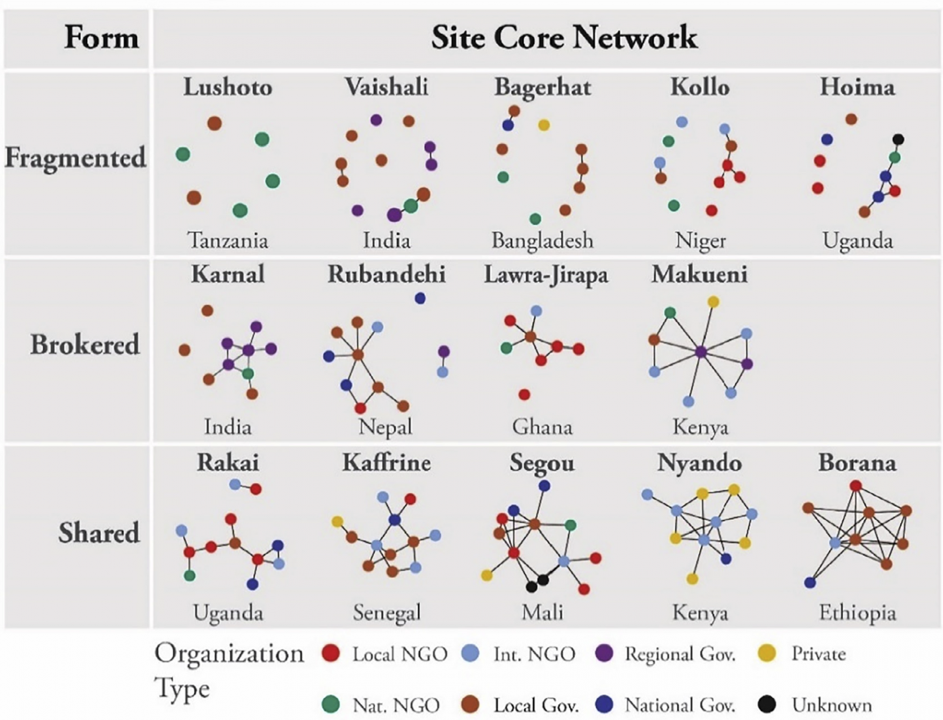

We found clear evidence for shared (high density, low centrality) and brokered (low density, high centrality) network structures, and surprisingly high number of fragmented (many isolated actors) networks. Each of these network configurations may have implications on how climate change resilience and agricultural development efforts are implemented and coordinated across the group of public and private organizations working within a given site.

All network types are observed in the CCAFS sites. Source: Rudnick et al. 2019

Local and regional organizations (both government and NGO actors) most often fill central leadership roles in networks with greater connectivity. This suggests these local and regional entities are necessary partners to involve in any new effort aiming to enter a community, as they hold the key to effectively coordinating on the groundwork. At the same time, INGOs play an important role in increasing connectivity across a site, specifically by partnering with different local/ regional organizations (rather than with other INGOs). These local-international partnerships appear crucial, to both gaining local trust and excitement for an initiative, as well as leveraging external resources and connections.

Finally, through this work, we also learned the necessity of collecting network data on the “periphery” organizations (i.e. community-based groups, farmer cooperatives, informal support networks in a community) who may be outside of the formalized, key actors, yet still provide critical connectivity between organizations via personal relationships, or who may be key links between community residents and organizations’ efforts. This indicates a key next step in studying agricultural development networks.

What's next?

To better understand why different network types exist, we need more measures of network structure over as many communities and time periods as possible. Thus, this work is being extended in the CCAFS Midline Surveys currently underway, to follow up on these networks and understand if and how they have changed over time.

To better understand the functional differences between fragmented, brokered and shared networks, it is critical for future research collecting network data to also measure network outcomes, so that we directly assess the effectiveness of different network structures for reaching specific goals. We can then compare the efficacy of organizations’ activities in sites where networks are well connected (i.e. shared or brokered networks), compared to sites where organizational networks are highly disconnected (i.e. fragmented networks).

Our next steps are to begin testing the effects of network connectivity and coordination on outcome variables collected by CCAFS at household and village levels, such as household food security and other indicators of climate analysis resilience.